The following is based on research that focuses on the Russian Orthodox Church’s response to the heroin problem in Russia, which the author considers in his new book “HIV is God’s Blessing”: Rehabilitating Morality in Neoliberal Russia (Berkeley, 2011). This post originally appeared at openDemocracy.

The Russian government is once more refusing to accept responsibility for yet another form of suffering it has imposed on its people – heroin use, addiction and the various associated health crises. It is doing its best to lay the blame on others for the drug use epidemic and ensuing HIV crisis by stepping up its criticism of the USA and NATO for not doing more to stop the flow of heroin from Afghanistan into Russia. This internationally staged political theatre is intended to create the illusion that Russia’s current HIV and drug use epidemics are a direct result of the war in Afghanistan. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Russia today has an estimated four million active drug users, one of the highest percentages in the world. The Russian Ministry of Health estimates that drug use rose by 400% between 1992 and 2002, that is, during the ten years prior to the USA/NATO invasion of Afghanistan. As early as 1999 it was perfectly obvious to international organizations working there that Russia was experiencing a wave of HIV infections related to injecting drug use. While in many parts of the world sexual contact is the primary means of transmission, in Russia about 80% of the estimated 940,000 people currently living with HIV were infected through injecting drug use. There is little doubt that Russia today is in the grip of an HIV epidemic. Most troubling is the UNAIDS report which indicated that, as of the end of 2002, Eastern Europe and Central Asia had the world’s fastest-growing HIV/AIDS epidemic. In this region, Russia has by far the highest number of people living with HIV/AIDS (in abbreviation PLWHA), and the fastest-growing number of infections.

Yet very little is being done about it. Despite a promised thirty-fold increase in budget allocation for HIV-related programmes in 2006, and again in 2008, the Russian government continues to underfund programmes and medical facilities related to HIV or drug use. Additionally, by focusing on the criminalization of drug use, Russian government policies are arguably contributing directly to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The majority of state funding goes towards anti-drug law enforcement, rather than treatment and prevention programmes. Such punitive policies tend to focus on users rather than dealers. Human rights organizations have been very critical of the long prison sentences handed down for the possession of very small amounts of drugs.

Related to this, and in fact the main reason why there is so much heroin in Russia today, is the deep and widespread corruption within the Russian police forces, border security, and legal institutions. The police are widely believed to work hand in hand with the so-called drug mafia. They certainly exploit drug users, who are regularly rounded up to fulfill monthly arrest quotas. In sum, Russian drug policies and the corruption endemic to the Russian legal system help create a situation in which injecting drug users (IDU) do all they can to avoid the world of official institutions, including the medical facilities that may be able to offer help.

Not that the medical facilities provide what they should. The ghosts of the Soviet medical system still haunt the Russian people, and particularly PLWHA. One of the remnants from those times is that PLWHA can only receive medical treatment at specific hospitals or specially designated medical facilities. In St. Petersburg, a city with probably the highest number of HIV-infected heroin users, there are three such locations – two hospitals and one ambulatory centre. Treatment at the centres will only be administered to registered PLWHAs. Care will be denied at any other state medical facility to anyone who is known to be HIV+ or to have contracted AIDS. Such assistance is often denied at privately-run paying facilities as well. This system not only perpetuates the already deep-rooted stigma attached to HIV or AIDS, but also leads to a general lack of knowledge, skill, perhaps even sympathy, on the part of those medical personnel who do not work at the AIDS Centres. The current medical system in Russia would seem to reflect the indifference of both government and society to the HIV and drug epidemics in their midst.

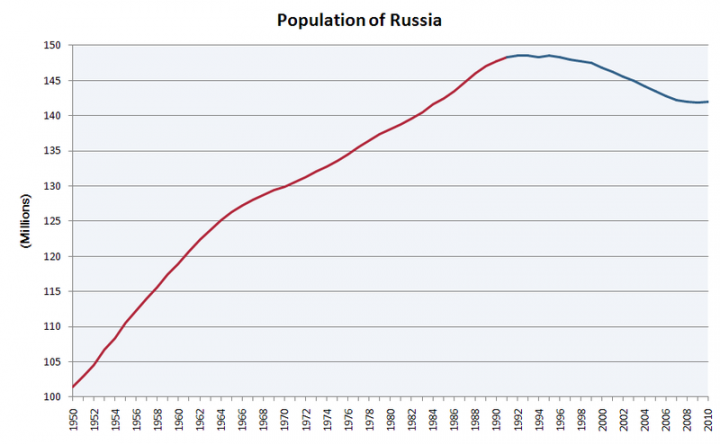

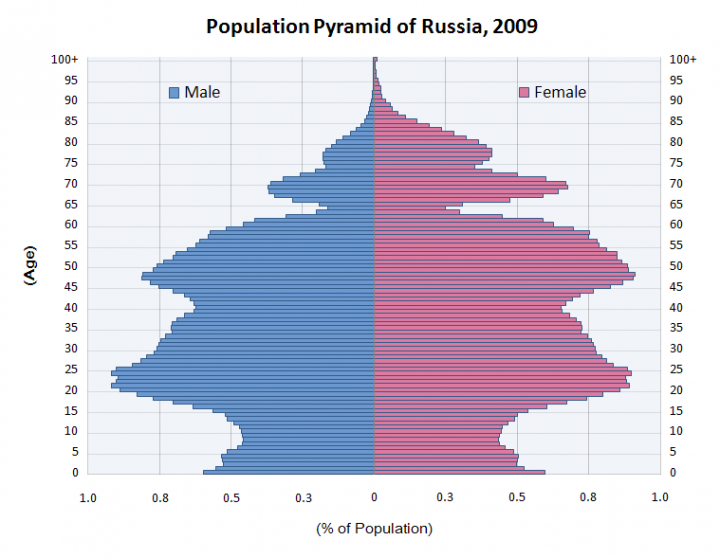

This has a deleterious effect on the already worrying demographic crisis in Russia — the first industrialized country in non-wartime or non-disaster conditions to experience such a sharp decline in its population. According to one estimate, the number of HIV cases in Russia over the next decade could rise to 8 million. This would amount to about 10% of the population. Even if such a high figure is never realized, HIV/AIDS will have a particularly pernicious effect on the Russian economy and national security, because it is overwhelmingly found in the younger members of society, who are already or about to become of working age. It should be noted that many young men begin injecting heroin and other drugs in the army.

So despite the Russian government’s recent phony public outbursts against the USA and NATO, the causes of the HIV and heroin-use epidemics are in no way related to the invasion of Afghanistan. The most obvious proof of this is that heroin-use in Russia reached epidemic proportions by the end of the 1990s, if not earlier. Significantly, the opening of the previously closed Soviet borders has meant that the Russian Federation is now one of the primary transit countries in the global drug market. Russia has become a key point in the activities of the exploding international global heroin market. This is explained not only by relatively weak border controls, illegal migration and rampant corruption, but also by its location between the Central Asian heroin exporters and Western European consumer markets.

Another significant factor is the socio-economic situation in post-Soviet Russia. Increased personal freedom, the upheavals of the transformation to a quasi-capitalist market economy, increased exposure to Western lifestyles including the glamourization of drug use, increased spending money for some, and a lack of hope in the future for others, have all contributed to the booming Russian heroin market. If the Russian government is looking to apportion blame, it had best begin with its own domestic medical and legal policies and practices. Unfortunately for millions of Russians, this is highly unlikely.

The effects of the breakup of the Soviet Union, alcoholism and the HIV epidemic have presented policymakers with a real dilemma.