Introduction

Michele Alacevich

Albert O. Hirschman died on December 10, 2012, after a long, eventful, and at times truly adventurous life. Born in 1915 Berlin as Otto Albert Hirschmann, he belonged to the last generation of upper-crust, assimilated Jews in democratic interwar Germany. As a young social democrat, he observed with increasing concern the polarization of the political life in postwar Germany before the collapse of the Weimar Republic. When Adolf Hitler seized power in 1933, seventeen-year-old Hirschman went to Paris and did not return to his native country until the late 1970s. In the following years, Hirschman would live in France, England, and Italy, fight in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side, and collaborate with the Italian and French Resistance movements. Meanwhile, he pursued his somewhat irregular studies in economics and the social sciences. From the United States, his adoptive country after 1941, he would travel further to Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa, while undertaking—after some initial difficulties due to his social-democratic sympathies—a brilliant academic career at Columbia and Harvard universities and the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton.

Besides crossing national borders and traveling through languages and cultures, Hirschman regularly crossed disciplinary borders, and today he is recognized as one of the most well-rounded and interdisciplinary social scientists of the postwar era.1 While Hirschman certainly was a development economist, the essays collected below show the fundamental coherence underlying the questions and methodological interests of his intellectual trajectory, well beyond the borders of development thought. Although Hirschman himself insisted on his propensity to self-subversion, he was nonetheless very consistent: to borrow from Fernand Braudel’s famous dictum, in Hirschman’s thought “tout se tient.”2 Nadia Urbinati shows this vividly in her analysis of Hirschman’s formative years and mental habits—a repulsion for dogmas, a propensity to question (as a basis for action not inactivity), and a sort of “rationalist boldness.”3 Hirschman’s heterodox position within an already heterodox discipline such as development economics in the 1950s, or—as Ira Katznelson put it—his “analytical amalgams” in studying the various interpretations of market societies, are obvious examples of this intellectual aptitude. Likewise, the incorporation of historical analysis for the sake of greater realism in the social sciences is a constant of Hirschman’s production.

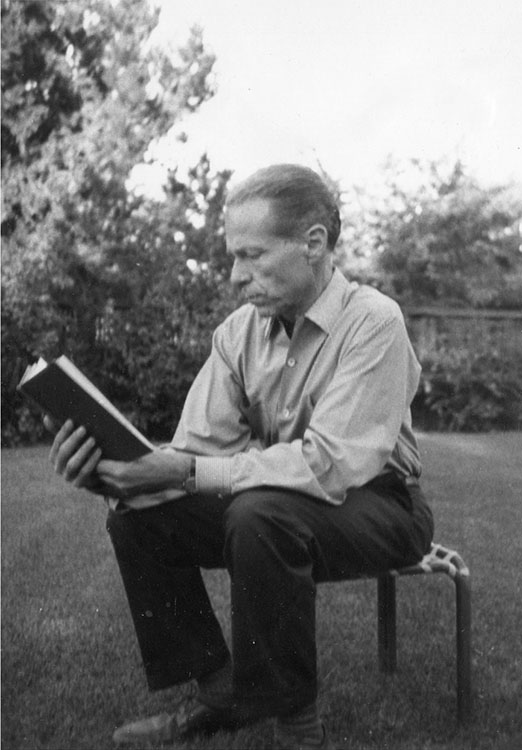

Fig. 1.

Nine-year-old Otto Albert Hirschmann in Berlin in 1924. All photos courtesy of Katia Salomon.

The same continuity and coherence is visible in a number of recurring themes in Hirschman’s research, as well as in the way specific ideas traveled from one phase to another of his intellectual journey. Hirschman often developed new research questions from intuitions he had only partially pursued in previous research. From this perspective, his work on development is particularly meaningful—Gradually he shifted his focus on “hidden rationalities” and “pacing mechanisms” from economic development (in The Strategy of Economic Development) to political reform-mongering (in Journeys toward Progress) to project implementation and appraisal (in Development Projects Observed ).4 Ideas on specific development issues later provided fertile ground for his work on the history of capitalist consumerism—as highlighted by Victoria de Grazia—and his analysis of the responses of individuals, firms, and organizations to lapses from functional behavior—as highlighted by Jeremy Adelman.

Each of the essays below deals with a specific period, or a specific work, from Hirschman’s long intellectual life, yet many connections are visible among them. This deep unity among a variety of themes is just a natural reflection of Hirschman’s work, and one of the reasons for his central role in postwar social sciences.

“Proving Hamlet Wrong”: The Creative Role of Doubt in Albert Hirschman’s Social Thought

Nadia Urbinati

Albert O. Hirschman was “a skeptic who preferred anomalies, surprises, and the power of unexpected effects,” phenomena he thought literature helps us see more easily than economic models do.5 Hence, Jeremy Adelman writes in his biography, Hirschman’s economist colleagues thought of him as a sui generis economist because he did not translate ideas into numbers, loved understanding complexity in social phenomena more than making predictions, and, moreover, used too many words. Hirschman greatly cared about the aesthetics of language. He was a social scientist immersed somehow in the nineteenth-century style of the mind, a century in which disciplines were not yet divided by high barriers and scholars wrote with equal competence on literature, history, politics, and economics. Hirschman was a humanist who read philosophers, novelists, and poets for hints into interpreting human emotions, for revealing insights into the relationship between interests and passions, and for indications of costs and benefits in economic behavior. Thus when he was asked by Daniel Bell to illustrate the character of his method, Hirschman answered that if he did not put his thoughts “into mathematical models” it was because “mathematics has not quite caught up with metaphor or language.”6

Adelman writes that this odyssey within words and languages (Hirschman mastered several with exquisite proficiency) mirrored his life, which was indeed like an odyssey—a life that began in 1915, in a city, Berlin, then lively and tumultuous, and ended in 2013, in the solitary woods of the Institute for Advanced Study of Princeton. Hirschman’s story was cosmopolitan by education, pleasure, and necessity. He was born and raised in an upper-middle-class Jewish family deeply assimilated into the German nation and wholly secularized (his father was a well-known surgeon with strong social ties in his city). Hirschman’s cultural background was German and European, grounded in artistic and literary culture (late in his life he started painting, and he was a talented painter who took the same pleasure in rendering colors and shapes as he did in analyzing human emotions and economic behavior). His forma mentis was oriented by the categories and concepts coming essentially from two centuries, the eighteenth and nineteenth, when social sciences and economics were born.

The Enlightenment (Scottish and French, but also Italian—he was familiar with the “economia civile” of Gaetano Filangieri and the work of Cesare Beccaria) and Romanticism (philosophical and literary) were his main reference points in addition to the work of the French moralists of the seventeenth century. And in the tradition of Karl Marx’s analysis of the bourgeois society, and, before that, eighteenth-century social science and political economy from Helvétius and Condorcet to Adam Smith and David Hume, Hirschman devised a historical reconstruction of the merging of uses of the term “interest” in economics, morals, and psychology. He aimed to coin a monolithic vision of interest as rational motivation that uses irrational impulses like passions and emotions as sources of energy to assess regularity, effectiveness, and continuity in individual behavior. His underlying guideline was Hegelian, as Hirschman wanted to decode individualism, the ethos of modernity that oriented moral as well as social behavior. The interpretation he inaugurated was motivated by the goal of retaining the priority of interest while emancipating it from the neoliberal view and, as a matter of fact, from any dogmatic view.

The cultural milieu of Hirschman’s family and early years in Berlin repelled dogmas and identity politics of all kinds and was inspired by curiosity and knowledge. The république des lettres was in its twilight then, but it was still alive when Hirschman was a student in Berlin’s lyceum. His beloved sister, Ursula, recalled later that as adolescents they were inspired by a sort of “rationalist boldness” and identified adulthood with emancipation from the “heavy fetters” of “family and tradition.”7 Albert and Ursula left Berlin in a mood that was consistent with their enlightened spirit.

The way in which a person expatriates reveals a great deal about him- or herself. Hirschman chose to leave Germany in April 1933—only four months after Adolf Hitler took power. In making that wise decision he was guided by what I regard as his primary mental habit, doubt—doubt concerning the new regime. Doubting, questioning, and a disinclination to trust the status quo—this led Albert and Ursula to take a vacation trip to Paris. That was the best decision of their lives, Albert told me in one of our several conversations. It is interesting to learn from Adelman’s book that brother and sister did not leave Berlin with the idea of exile; rather, they left in the way that students do when they go abroad to experience the world. Albert and Ursula moved to Paris as students rather than émigrés, but as Paris was quickly becoming the center of political exile for European antifascists, they were soon political exiles themselves. Their “collective apartment” became the harbor for a steady stream of guests—first, “Germans bearing the latest news from the political front,”8 then Italian antifascists, among them militants of the liberal-socialist movement Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Liberty), and also Eugenio Colorni, whom they had met years earlier in Berlin, where he was a visiting student in philosophy. Colorni would become Ursula’s first husband and one of Hirschman’s most important mentors.9

I want to touch again on the mental habit of doubting, which is in my view crucial to understanding Hirschman’s “self-subversive” method in morals and politics. In a time in which people were driven by strong ideological faiths and nothing seemed to work without the pre-defined guidance of a Weltanschauung, Hirschman persisted in living outside of and without any Weltanschauung. His poles of attraction were neither party nor church nor fraternity affiliation but rather person-to-person relations, such as friendship and dialogical conversations, love of fine arts, and attachment to the eighteenth century’s causes of antimonopoly and freedom from the bonds of any ancien régime ideology (which Albert deconstructed effectively in The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy [1991]). These were the sources of inspiration and the components of Albert’s habit of the mind, the seeds of what he himself called “self-subversion of the self.” In one of his autobiographical essays, he traced this habit of the mind back to Colorni, his friend and brother-in-law.10 Colorni offered Hirschman what the latter was searching for from the time of his early youth in Berlin, when he had heard his father assert that he did not have aWeltanschauung—a daring statement in a country and a time in which nothing seemed workable without the guidance of a faith or unquestioned loyalty.11

As a scholar of social and economic sciences, Hirschman was as refractory to deterministic approaches as he was to Weltanschauung. On this he never changed his mind. He admired Carlo Rosselli and the liberal-socialist ideas of his movement, Giustizia e Libertà, precisely because they were militant in a political cause without embracing any ideology except the struggle for liberty—”liberty” indeed to doubt and exit (but also to say no to engagement and to indifference if necessary). Perhaps, as Hirschman said later, the only “rigidity” he wanted was that of antifascism. Doubt played a central role for those “voluntarist” antifascists to both mobilize them against tyranny and understand their times of “crisis” and totalitarian madness; doubt and uncertainty induced them to look for ways out. “Voice” and “exit” would be, Hirschman believed, the best assurance of loyalty because they best prevent obstructions to possibilities: possibilism was to him an intellectual temperament more than simply an idea, and its sources were rooted in the years of his exile first in Paris and then in Trieste. Petites idées, “small pieces of knowledge,” rather than worldviews, were the key to understand human relations, personal and social: “The petites idées was ‘a really key thing throughout Albert’s life,’ according to his wife, Sarah, ‘that he told me almost on the first day I met him, when we talked about Eugenio [Colorni].’ “12

In Adelman’s excellent biography, we see that this mentality guided Hirschman in the various activities he performed throughout his life: for instance when he collaborated in the international resistance in Marseille and falsified documents so well that he generated suspicion in the police. Hirschman was proud of that falsifying proficiency, as if he wanted to prove that even the most perfect system could be fooled by not even very sophisticated means; and he was proud for having contributed to smuggling many Jews out of Europe with such stratagems. The mentality of possibilism and boycotting certainties and dogmas—in a word, self-subversion—likewise shaped his life after the war, when Hirschman gave up a normal career as an academic and opted to work in developing countries in South America, Asia, and Africa. He thought of himself as a traveler in search of challenges and problems to be detected and solved, and of limits to overcome. He tried to view things from a peripheral perspective, and he recognized that advances in one direction were often accompanied by setbacks in another. His inquiring mind was driven by the pleasure of questioning his own certainties and those of others, in the attempt to find traces of truth in petites idées.

One of Hirschman’s preferred verbs was “nibbling,” opposed presumably to the Pantagruelian way. “Nibbling is actually a good term” for the knowledge of social facts and tendencies because there is no overall valid solution; “historical experience provides us with occasional hints and discoveries, but they are different for different societies and for the same society at different times.”13

Hirschman’s propensity for self-subversion had an important impact on the deliberative view of democracy, although without premeditation on his part. His writings convey the view that in a democracy opinions are not fully formed in advance but derive from a process of deliberation. He criticized Anthony Downs’s economic conception of democracy, particularly the idea that one advantage of political parties was that they “offer citizens a full range of ready-made and firm opinions on all the issues of the day.” Perhaps we may appreciate, Albert observed, the time-saving feature of political parties and its opposite free-rider model, yet we cannot avoid thinking that this saving actually comes at a considerable cost. So, he concluded, “we express our doubts about the value of the Downs mechanism by designating those who take advantage of it as ‘knee-jerk liberals’ or ‘knee-jerk conservatives’ . . . Introducing the knee-jerk concept complicates the appraisal of the benefits that flow from having opinions.”14

Fig. 2.

Albert Hirschman and his wife Sarah just before he was dispatched to North Africa, circa 1943.

Among the most important of the many insights we owe to Hirschman is that which deems deliberation and the formation of opinions to be goods in the sense that they provide us with other kinds of goods such as liberty, self-respect, the sense of empowerment, or simply the pleasure of changing our opinions and casting doubts on dominant opinions. Yet to Hirschman, indifference toward and changeability in one’s opinions were not always bad either. Indeed, as we may infer from his reasoning, if opinions are like goods we produce for our public and private well-being, we should expect that they tend, like other goods, to be sometimes overproduced; and when we face overproduction of “opinionated opinions,” indifference and disbelief can turn out to be useful remedies. What is therefore generally met with contempt—such as political indifference or vacillation in one’s opinions—can present us with an invaluable good—a healthy distance between our mind and the mind of the public. This can strengthen the social fabric rather than rend it. Acclimating people to seek solutions through open discussion, Hirschman wrote, strengthens their loyalty to democratic procedures and principles because those procedures and principles guide and make sense of the rivalry people learn to value: democratic debate and antagonism play an unseen and unplanned unifying role in that they “produce themselves the valuable ties that hold modern democratic societies together and provide them with the strength and cohesion they need.”15 Voicing objections and rejecting unquestioned truth were also means of countering people who aim at “winning an argument rather than . . . listening and finding that something can occasionally be learned from others. To that extent, they are basically predisposed to an authoritarian rather than a democratic politics.”16

Thus Hirschman regarded skepticism and doubt as hygiene and food for a searching mind. He likewise saw them as motivation for action, according to an intellectual habit that he himself defined as an “exercise in self-subversion” and his young antifascist friends practiced in their perilous political action, “as though they set out to prove Hamlet wrong: they were intent on showing that doubt could motivate action instead of undermining and enervating it.”17

A Social Science of Complementarity and Contradiction

Ira Katznelson

I should mainly like to focus on Albert Hirschman’s May 1982 lecture, originally titled “Rival Interpretations of Market Society: Civilizing, Destructive, or Feeble?,” which was published in December of that year in the Journal of Economic Literature.18 Having been invited by François Furet to deliver the fourth annual Marc Bloch lecture at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Hirschman collected comments on an early draft from Clifford Geertz, Mark Granovetter, Theda Skocpol, and Michael Walzer, a cast not many economists would have consulted. Slightly retitled as “Rival Views of Market Society,” the essay provided the title for a collection of his writings published four years later, where it was paired in part 2 with the paper “Against Parsimony,” which Hirschman had presented at the American Economic Association annual meeting in 1984, an intervention subtitled “Three Easy Ways of Complicating Some Categories of Economic Discourse.”19

Read together, as he clearly intended, these two essays reveal as well as any of Hirschman’s writings the kind of social scientist he was, and the type of social science he advocated, a social science of analytical intellectuality—the analytical marked by a penchant for sharp and revealing distinctions and typologies brought into interaction; the intellectuality marked by a restless curiosity and a remarkable range of reading and reference in political theory, economics, social theory, history, sociology, and more. In his hands, intellectual history was a prod to analytical reason; and analytical reason was the means to make sense of the range of human ideas and practices. Together, these traits characteristic of Hirschman’s social science produced work that offers some of the best extant examples of how to reason within a field of tension marked, on the one side, by the pole of frugal and portable theory, and, on the other, the density of proper name history and human circumstances.

The “Against Parsimony” essay opens this way: “In his well-known article on ‘Rational Fools,’ Amartya Sen asserted that ‘traditional [economic] theory has too little structure.’ Like any virtue, so he seemed to say, parsimony in theory structure can be overdone and sometimes something is to be gained by making things more complicated. I have increasingly come to feel this way.”20 Hirschman proceeds to discuss changes in preference, types of action, and public morality required to deal with “realms of economic inquiry that stand . . . in need of being rendered more complex.”21 And he concludes by arguing that all the complications he has proposed possess a common structure, for they “flow from a single source—the incredible complexity of human nature which was disregarded by traditional theory for very good reasons, but which must be spoon-fed back into the traditional findings for the sake of greater realism.”22 His readers had seen this complexity earlier when the “silent scanner” of economic theory had been augmented by the verbal and nonverbal communication and persuasion tools of exit and voice; and it appears in this essay’s concern for noninstrumental action and behavior melded with instrumental action and behavior.23 “In sum,” Hirschman concludes, “I have complicated economic discourse by attempting to incorporate into it . . . basic human endowments and . . . basic tensions that are part of the human condition. To my mind, this is just a beginning.”24

What it means to reason analytically in a manner that is not too parsimonious is exhibited in the rival interpretations essay. Here the object is the central economic system of modernity—market capitalism—and the subject is how its meaning has been variously interpreted in clashing but not wholly irreconcilable ways.

Hirschman considers four views. First is that of capitalism and its commerce as “a civilizing agent of considerable power and range”—what he labels as the doux commerce hypothesis identified with Montesquieu, Condorcet, and William Robertson, among others.25 By attaching people through mutual utility, commerce promotes reason, civility, prudence, and manners. Commerce is a moralizing agent that helps capitalism function effectively for the larger good. Next, Hirschman contrasts this complex of early modern ideas with the later “Self-Destruction Thesis” articulated by thinkers as diverse as Karl Marx, Joseph Schumpeter, and Fred Hirsch, which views “capitalism as a wild, unbridled force which, having swept everything in its path, finally does itself in by successfully attacking its own foundations.”26 Third is the “Feudal Shackles Thesis,” also found in Marx and Schumpeter, but additionally in Alexander Gerschenkron, Georg Lukács, and Arno Mayer, which sees capitalism as limited by precapitalist structures, social relations, and mores, thus making capitalists and capitalism less than they should be in a commercial world. Finally, Hirschman identifies “A Feudal Blessings Thesis,” which Americanists can read in Louis Hartz, and which has also found voice in writings by Perry Anderson, a view that sees precapitalist values, including those that generate tight social bonds and trust, as key elements both in making capitalism work and in shaping a decent society—features that can best be observed when feudalism is absent, as in America.

These views, each of which has been deployed for ideological purposes, are not, in Hirschman’s hands, simply rival or alternative. The beauty of his essay lies in the manner in which he declines to choose among apparently rival conceptions but instead constructs connections and attends to contexts and particularity. All four, together, can enrich our understanding of modern capitalism. These are not “a jumble of theses” but have a close logical and temporal relation. “I have essentially dealt with four types of theses or theories and have represented them in a sequence such that each successive thesis is in some respect the negation of the preceding one . . . Rather wondrously, the various ideologies . . . end up composing a complete pattern . . . It is as though four blindfolded children did a perfect job jointly coloring a coloring book.”27

Further, Hirschman reduces their contradictions and conflicts by insisting that, notwithstanding key aspects of incompatibility, “each might have its ‘hour of truth’ and/or its ‘country of truth’ as it applies in a given country or group of countries during some stretch of time.”28 And he points out that “this is actually how these theses arose, for all of them were fashioned with a specific country or group of countries in mind.”29

Each, moreover, can be given its due in a more profound way. “It is conceivable,” Hirschman writes, that “even at one and the same point in space and time, a simple thesis holds only a portion of the full truth, and needs to be complemented by one or several of the others, however incompatible they may look at first sight . . . Now the task is to explore whether it is at all possible and useful to combine the theses that constitute those contradictions.”30 This is a plea for a social science of analytical amalgams, noting that “the balance is likely to be different in each concrete historical situation.”31

He thus concludes “Rival Views” this way:

It is now becoming clear why, in spite our lip service to the dialectic, we find it so hard to acknowledge that contradictory processes might actually be at work in society. It is not just a question of difficulty of perception, but one of considerable psychological resistance and reluctance: to accept that thedoux-commerce and the self-destruction theses (or the feudal-shackles or feudal-blessings theses) might both be right makes it much more difficult for the social observer, critic, or “scientist” to impress the general public by proclaiming some inevitable outcome of current processes. But after so many failed prophecies, is it not in the interest of social science to embrace complexity, be it at some sacrifice of its claim to predictive power?32

Between Consumption and Commerce: In Honor of Albert Hirschman

Victoria de Grazia

If I express my debt to Albert Hirschman by recalling how I became acquainted with two often-overlooked, awkwardly jointed dimensions of his work—namely, consumer behavior and commerce—I can better underscore the fruits that rereading his whole oeuvre will yield for anybody interested in reconceptualizing the history of market societies. When he and I first met in the spring of 1987 while I was a fellow at the Davis Center at Princeton, I would have described myself as an American-born, European-inclined historian and moralist, and he, a European-born, somewhat Americanized, social scientist and moralist. For a long time, I had been interested in understanding the interplay of force and persuasion in legitimating established order; the latest step in this trajectory was to understand the nature of U.S. hegemony across the North Atlantic world over the twentieth century as a function of the perceived superiority of the American model of mass consumer society.

Hirschman had long been interested in the mix of motives and actions that led people to challenge established order. In effect, as I later began to understand, he worked in two ways. One way was as an economist, to bring together theories of supply and demand from the marketplace with theories of the social contract from the political realm, his goal being to generalize about social action. The other way was as a historian, who in the study of the long-standing querelle of social theorists, arising out of the eighteenth century over whether market created or destroyed human bonds, sought to come to some conclusion about whether these contrasting positions could be reconciled by fusing market and government in more solidaristic economic relations.

The mid-1980s were an important moment for thinking about the consumption side of the question. No issue was more vexed for social critics, activists, and scholars, not because American social critics had not been writing about the perils of mass consumption to democracy over the previous three decades but because the arrival of what was variously labeled as a postmaterialist, post-Fordist, flexibly specialized, “new-economy” society appeared to signal that, in the advanced Western world, workplace interests and identities were yielding to consumer interests and identities as drivers of subjectivities and social action. If it is true that critics of American capitalism from a social-liberal perspective—one thinks here of the tradition running from David Riesman to John Kenneth Galbraith—gave significant weight to consumer sovereignty and consumer-directed movements, the burst of new studies coming out of history, economic anthropology, and sociology began to do more and more empirical work on the topic as well as to divide sharply over whether mass consumption was associated with the dimming of mass politics or the possibility of new solidarities and identities.

In addition, there was increasing skepticism about whether any of the conventional economistic understandings of consumer behavior deriving from neoclassical notions of scarcity and marginal utility curves were suited to conceptualizing historically how people exchanged goods through the marketplace and how these gave meaning to their lives—much less how these meanings were inflected by every kind of asymmetry of power, from class and status to race, gender, and religion. Consequently, although the work that brought me to Princeton regarded consumption (specifically, to study the impact of U.S. corporate marketing and advertising on European models of consumption), and although Albert Hirschman had written a great deal on consumption as well as commerce, I had not even considered reading his work until I actually met him.

Anybody who reads the chapter of Jeremy Adelman’s biography discreetly titled “Body Parts” will get some glimpse of Hirschman’s ineffable charm. That Hirschman’s gaze was so penetrating, that he was such a good listener, so curious, and so welcoming to the outsider, that hisflâneur-like figure could work intellectual magic, transforming the bleak flagstones in front of Firestone Library into an impassioning Euro-intellectual space—all of that was a jolt to thinking. That effect was all the more pronounced in my case because my immediate subject, U.S. corporate advertising in interwar Europe, was not a typical topic at Princeton’s Davis Center for Historical Studies. Perhaps I was being oversensitive, but the then director, the great British historian Lawrence Stone, seemed to regard branding and marketing especially disdainfully as not being culture at all, or not in the sense of the Center’s topic “The Transmission of Cultures.” Later, in the way of apology for his impatience with the subject, he let on that his father had worked as an advertising copywriter at the London office of J. Walter Thompson, been laid off during the Depression, and, like one of those market-battered figures in the grey flannel suit literature of America’s 1950s, had deserted the family. By contrast, Hirschman, being a true Berliner and thus devoid of Bildungskultur hang-ups about the market, had immediately offered that his father, a prosperous Jewish doctor, had driven a Buick, which was his charming way of saying that his family knew the value of the elegant positional good.

Recalling his work on development issues, Hirschman also introduced me to a figure influential to his own formation, namely, the heterodox economist James Duesenberry, who, in 1949, picking up on Thorstein Veblen, had written about how consumers’ emulation of the practices of others could work as a “demonstration effect,” affecting propensities to spend and savings rates. This insight, in turn, led to Ragnar Nurkse, who in 1953 spoke of an “international demonstration effect” that might have people in developing societies responding to their exposure to new articles or new ways of meeting old wants by coming under pressure to change their living standards.33

The truth, however, is that at the time, I was ill-equipped to grasp the real scope of Hirschman’s work, much less that he was not really interested in consumer behavior per se. It could have been because I was under such time pressure that I could not read the sizable body of his essays, even if I had possessed the social scientific culture to do so, that my leave was short, and the scholarly day very brief between planting my two-year-old daughter at the day care center and policing her once she returned to keep her from plunging into Lake Carnegie in her wild pursuit of Canadian geese. But it was also true that as a historian, I was opportunist and piecemeal, picking up what was useful to give courage to my analysis rather than to unpack a whole oeuvre, Hirschman’s, to understand its conceptual stakes and genealogy.

In reality, Hirschman was working along two lines of thought that he never fully reconciled. The first line was that of a political economist who, in his interest to generate an overall theory of action, sought to conjoin the analysis of social action based on consumer behavior (which had individuals demonstrating their discontent by changing their preferences or exiting the market) to an analysis based on political behavior (which would have people standing firm to voice their grievances), with both complicated by the tug of loyalty, whether to brand, family, party, or even nation. The other line of thought saw him as a historian of ideas of the market, probing the alternate understandings of the market, viewing it at one and the same time as productive of civilized human exchange and catastrophically destructive of values and relations. The mode of analysis underlying his first line of interest was derived from a basically essentialist ahistorical notion of consumer behavior, which was the dominant way in which market exchange was conceived in the United States in the wake of World War II, to the neglect of more solidaristic ideas. The mode of analysis underlying his latter line of interest was, by contrast, historically and socially constructed, derived from studying how over two centuries mainly European social theorizing had conceived of really existing markets. Hirschman moved between one and another lines of inquiry. Even in in his Rival Views of Market Society and Other Recent Essays (1986), the two coexisted in increasingly expansive reflections on each trajectory rather than coming into conversation with one another.

My sense is that, ultimately, Hirschman was trying to bridge in his own mind two very different ways of understanding market forces: one was from his Old World, that of commercium—the “together” and “merchandise” of doux commerce—which, in an idealized form, differed from the disembedded market but also from the monstrosity of mercantilist military states; the other, from the New World, that of consumer sovereignty, which, if its premise is correct, rests on the right of consumers as individuals to pick and choose and which can act as the basis of consumer democracy (a term he would have never used) if exercised with a carefully articulated mastery of exit and voice.

His hopefulness surely arose from what we might call Hirschman’s California experience—which saw from the perspective of Stanford and Berkeley coexisting in time, if not in the same public space, two kinds of protest: one, under the influence of Ralph Nader, mobilized consumer protest against General Motors and other giant corporate enterprises; the other mobilized political protest against the Vietnam War. As Hirschman implicitly recognized in Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970), in a point to which he would return in successive responses (the most capacious of which is found in “Exit and Voice: An Expanding Sphere of Influence,” in Rival Views), neither form of protest was ideological in the Old World sense: the archetype of the hippy, who exited to protest displeasure, in effect copped out; and the more heroic Eugene McCarthy figure, who, by exiting the constraints of the Democratic Party, created a substantial voice of protest.34 If he could never effectively turn this analysis of human action against entropy into a more generalized theory to explain what, short of powerful doctrines, ideological master plans, or technologies, motivated collective actors to bring reformist social change, Hirschman nonetheless stood as an optimistic counterpoint for the dismal declensionism of post-Vietnam contemporaries such as Christopher Lasch in The Culture of Narcissism (1979) or the Richard Sennett of The Fall of Public Man (1977).35

In sum, Hirschman the historian who focuses on the critique of markets, who wonders how values and social relations can be re-embedded in market mechanisms, who engages with the larger and larger variety of “really existing” market societies, struck me as ultimately the more satisfying Hirschman, looking out from the United States to understand the different national traditions, social structures, and cultural values that contribute to “a considerable, if somewhat hidden, element in the overall resilience of market societies.”36 From 1977, as he published “Political Arguments for Capitalism before its Triumph”(to quote from the subtitle of The Passions and the Interests), he was probing several developments by way of his reading of the evidence from epochs of transition: the ideological processes through which markets were moralized, how human labor became alienated wage labor, how wealth was accumulated and controlled, how private came to be separated from public goods; and how terms like “passion” and “vice” gave way to the bland notions of “advantage” and “interest.”37

Hirschman’s notion of rival markets worked not only for Europe but also for the twentieth-century interregnum that saw U.S. hegemony rising and the Europe of the Great Powers collapse. He could discern another epoch of that abiding conflict in the wake of 1989, as social democracy began to clash with neoliberalism in the aftermath of the worldwide crash of state socialism. In the new divide that is evident from the crisis of financial capitalism of 2008, he would surely probe deeply into what he called “the unbalanced acts of life” and—as an optimistic pessimist or, better, a pessimistic optimist—he would offer cautious, “possibilistic” but penetrating reflections.

Unfinished Work: Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

Jeremy Adelman

Albert O. Hirschman’s most famous work was Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Published in 1970 by Harvard University Press, it immediately sparked debates on themes as varied as understanding immigration, dissidence behind the Iron Curtain, and the deterioration of the American automobile industry. Many doctoral dissertations would cotton on to the famous verbal triad; indeed, the words would become so commonplace that their original combination was often forgotten. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty is generally regarded as one of the classics of twentieth-century social science.

The book was a transitional one for its author. Hirschman had made his mark as one of the most original thinkers of the economics of development—which was a big deal in the 1960s, the “development decade.” He was also an important voice in the hemisphere, urging opinion leaders in the United States to think more deeply and empathetically about Latin American neighbors, and became a sympathetic critic of some of the fatalistic trends among Latin American social scientists. What Exit, Voice, and Loyalty did was catapult Hirschman beyond the precinct of an economic subfield, and beyond a specific region—to become a more universalizing figure who transcended disciplinary bounds.Exit, Voice, and Loyalty brought Hirschman as close to academic fame as one could imagine in an age in which the divas of the Ivory Tower still thought of themselves as professors first and media figures a distant second.

But there was a second way in which Exit, Voice, and Loyalty represented a transition. Hirschman was a writer who seemed to command such a confident grasp of the social sciences. To think of his masterworks, from Strategy of Economic Development to The Rhetoric of Reaction, is to feel oneself in the presence of a rare combination of self-assuredness and humble self-doubt, which Hirschman would late in life coin as “self-subversion.”38 And yet the book that drew most from his auto-interrogating style was Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. Hirschman returned to it recurrently for the next several decades not so much because he thought the insights applied (as they did) across a wide array of cases and historical moments, but because there was a seam of dissatisfaction and unsettlement sewn into its making.

It helps to recall the moment and motivation behind the work. It was not just the undoing of the postwar consensus, the rise of nonviolent and violent dissent, and the unraveling New Deal coalition that caught Hirschman’s attention. There is no doubt that student unrest, protest against the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the emergent consumer movement shaped his thinking. But Hirschman’s field of development was also being singled out for its failures and disasters. Hirschman had not anticipated this. Indeed, in a little-known paean, Development Projects Observed (1967), Hirschman had positively gushed about how big projects could change the fortunes of the Third World—including a World Bank–funded railway project in Nigeria.39 No sooner did that book roll off the presses, however, than the Biafran civil war erupted. Not only had Hirschman failed to see it coming (though his field notes are filled with observations about simmering unrest); Development Projects Observed was a defense of project-based development lending. Hirschman was appalled and ashamed at his own oversight.

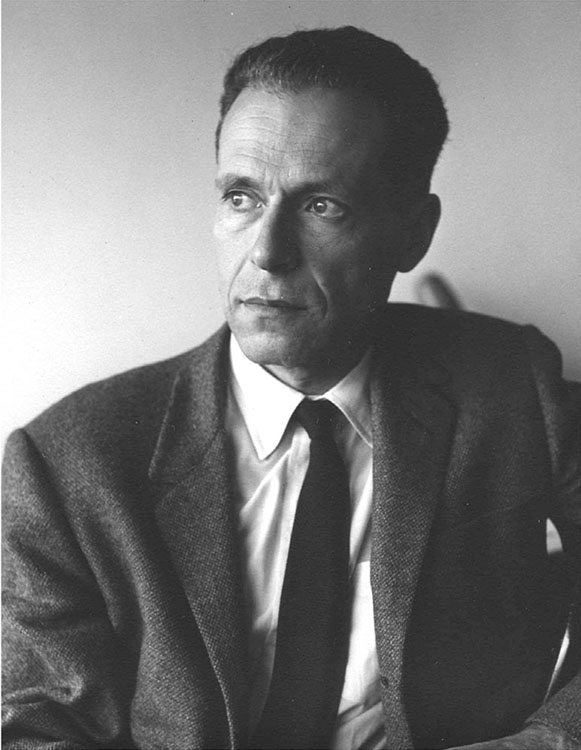

Fig. 3.

Hirschman in 1969, during his stay at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford, while working on Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (1970).

In response, he sought out ways to understand behavior in more complex ways, drawing upon psychology (a perennial interest), marketing, politics, and economics— specifically the work on the theory of the firm. It is worth stressing the conjunction between the keywords of the title—Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. Indeed, Hirschman was constantly conjoining seemingly disparate words, urges, and forces. Passions andinterests. Action and observation. Skepticism and engagement. What interested him were the tensions and disequilibria generated by an understanding of ourselves as complex beings, mobilizing and “checking out,” being citizens and customers. Sometimes we might even act as customers in the political domain or use strategies more familiar to social movements in the face of unresponsive corporations. This was the beginning of a long process that would see Hirschman question the boundaries that separated the disciplines of the human sciences and marked, one might say, Hirschman’s exit from his own home discipline. That it overlapped with the demise of development economics was not mere coincidence.

While this is not the place to summarize the contents of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, two features deserve some emphasis because they mark how Hirschman would look for ways of charting alternative futures, especially as the optimistic 1960s gave way to the more pessimistic 1970s. One grew directly out of the failed observations about development in Nigeria. As Hirschman thought about the structure of firms, he wondered whether some conditions favored certain kinds of responses over others— arguing that competitive settings favored “exit” while monopolies tended to yield to “voice.” But rather than turn this into a mechanical formulation with predictive powers, he insisted that both exit and voice presented firms and organizations with opportunities to recuperate or degenerate. It was up to price-makers or rulers to treat the threat of voice or exit as deterrents to deterioration and a chance for recovery. This was important because Hirschman wanted to signal the possibility, from multiple positions, for reform and change.

Second, consider the significance of “slack.” This, in fact, was an old theme of Hirschman’s development thinking. The prevalence of slack and unused capacity should be, he felt, a helpful departure point—observing that decay and decline were natural, not pathological, tendencies. All organizations become less efficient and lose their surplus-producing energies; it does not take monopoly to breed lethargy. Treating decline seriously was often a premise for pessimism. For Hirschman, it could be turned around; thinking about slack meant there was room for corrections and reforms that could in turn take different forms. What was important was not to be dogmatic about any necessary solution or pathway—not to presume that competition was always good or that giving power to the people would solve any problem.

The openness of the work lent itself to many directions and permutations—and certainly helps explain why Exit, Voice, and Loyalty could have such a fecund career. Hirschman revised and reformulated it across many years. But there was another reason why the work was the emblem of his self-subversion. One might say that it was unfinished because it had built-in blind spots. There was a tendency, to which Hirschman contributed, to accent the first two action verbs at the expense of the noun following the conjunction. Exit and voice overshadowed loyalty. This was, and became, a problem. One of his manuscript reviewers noted this and urged him to consider at least a coinage like “re-enter.”

It is tempting to conclude that a fiercely secular, cosmopolitan, multilingual, “global” intellectual like Hirschman, whose career was so iconic because he could cross national and cultural boundaries with such ease, would have less understanding of loyalty. After repeated uprootings from Germany, France, Italy, the United States, and Colombia, neither country nor God could command much of his energy.

But a certain restlessness suggests that he was not altogether comfortable with leaving loyalty as a passive, default condition from which a citizen-customer springs to action with voice or exit. For one, Hirschman began to see that loyalty could be good for organizations and societies—and in fact that the threat of exit, far from holding leaders accountable, could have the opposite effect. We know that he worried about this because when the German publishers of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty asked him to compose a special preface, Hirschman drew the connection between his verbal formulation and his own personal experience as a Berliner faced with the rise of Hitler. In the first draft of that preface, he noted that the decision to leave the German capital for France, indeed the flight of many of his activist confrères (Hirschman was a militant in a youth wing of the German Social Democratic Party), meant that the departure of young campaigners, many of them Jews, drained the most vital political forces from the Jewish community, and thus made it more vulnerable to persecution. It was an odd argument. Hirschman had never self-identified as a Jew and would certainly not have an attachment to the Jewish community in Berlin. Yet not only was he taking on some blame for what happened after 1933; he was pointing to the more active features of loyalty—ones that blurred the line between it and, say, voice.

The troubled demise of the Weimar Republic was on his mind through the 1970s—not surprisingly as the word “crisis” was on everyone’s lips after 1973—as Exit, Voice, and Loyalty made its rounds. The loyalty question kept coming back. During a trip Hirschman took to Russia in 1977 with his wife Sarah, the issue of commitment and struggle haunted him. One night, during a thunderstorm in Moscow, Hirschman bolted from his sleep mumbling about Marx’s ideas of violence and revolution, echoes of fevered debates about how to defend German democracy in 1933.

But it was not just the relationship between voice and loyalty that was at stake. So too was the tie between exit and loyalty—what one might see as the most dichotomous of choices. By the late 1970s, a different personal experience, one which Hirschman had kept effectively under wraps, was coming to light: his involvement as Varian Fry’s right-hand man in the rescue of refugees from Marseille in 1940. Many hundreds were saved from the Vichy police and the Gestapo. But the operation raised some basic questions about how the practice of exit—the economic or “market” response to deteriorating organizational life—can also serve as a gesture of loyalty to something else, like a cause.

Over the course of the career of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, Hirschman’s attention shifted away from a contained view of economics to one that explicitly engaged with broader issues of language and democracy—an economieélargie, as he would tell an audience in Paris in the mid-1980s. The brilliance of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty was to have caught the temper of the times as the mobilizations of the late 1960s gave way to the 1970s. But one might equally say that its brilliance lay in setting the stage for a field of analysis that would unsettle the relationship between democracy and capitalism. It offered a vocabulary and heuristics for new insights and possibilities. And it unfolded a research agenda for Hirschman to think about some tensions that were at once deeply personal and political, to consider the possibilities of a social science that was more open and experimental, while admitting its loyalties to underlying values and purposes.

Hirschman’s Development Journey and the Rise and Fall of Development Economics

Michele Alacevich

Albert Hirschman was a Renaissance man, and his scholarly trajectory was characterized by—in fact, built upon—working across disciplines (or “trespassing,” in Hirschman’s words). Today, as Cass Sunstein wrote, Hirschman is principally known for four remarkable books all published after 1970: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970), The Passions and the Interests (1977), Shifting Involvements (1982), and The Rhetoric of Reaction (1991).40 Yet, like everybody, Hirschman had to start somewhere: as it happens, his first professional identity in the 1950s and 1960s was that of a development economist. His contribution to the early development debate had such a great significance that he is now considered a founding father of the discipline. Moreover, his early reflections on development issues influenced in important ways many of his subsequent writings.

Hirschman’s formative years in development were as momentous as serendipitous. In 1952, when he moved to Colombia as an economic expert for the World Bank, he was, in his own words, “without any prior knowledge of, or reading about, economic development.”41 He joined a small group of foreign experts who had lived in Colombia for many years and had been part of a groundbreaking World Bank mission to that country in 1949. The mission produced a voluminous report on the social and economic conditions of Colombia, which recommended a comprehensive development plan to lift the country from the vicious circle of poverty it seemed to be locked in. The idea, in a nutshell: “Economic, political and social phenomena are so inter-related and interwoven that it is difficult to effect any significant and lasting improvement in one sector of the economy while leaving the other sector unaffected . . . Poverty, ill health, ignorance, lack of ambition, low productivity are not only concomitants—they actually reinforce and perpetuate one another.”42

During his Colombian years, Hirschman felt increasingly at variance with this comprehensive approach—by then known as “balanced-growth approach”—mainly because he had serious doubts that it could actually work in practice. In 1958, he waged a full-frontal attack against it in his The Strategy of Economic Development. “Development,” Hirschman wrote, “presumably means the process of change of one type of economy into some other more advanced type,” whereas “the balanced growth theory reaches the conclusion that an entirely new, self-contained modern industrial economy must be superimposed on the stagnant and equally self-contained traditional sector.” The balanced growth theory seemed incapable of explaining the evolutionary process of economic growth, and thus, Hirschman concluded, “fail[ed] as a theory of development.”43

Hirschman’s focus was instead on what enables change. He highlighted what he called the “inducement mechanisms” and the “linkages” that can help entrepreneurship and growth spread from one sector of the economy to another. He was not searching for the missing ingredients of a well-balanced development recipe but—as he put it—for “resources and abilities that are hidden, scattered, or badly utilized.”44 In other words, this was not as much about transferring financial resources to a country as it was about mobilizing resources already available but hidden.

Fig. 4.

A portrait of Hirschman by the Colombian photographer Hernán Díaz, taken in Bogotá as Hirschman was working on Journeys toward Progress: Studies of Economic Policy-Making in Latin America (1963).

Strategy was hailed by many as a refreshing change of perspective in the early development debate, and even critics could not dismiss it. The book became one of those rare publications that have the power to frame a whole debate. Yet applied development policies in the field were not as mutually incompatible as the theories from which they descended: as it happens, supporters of balanced growth reasoned in terms of sequences of development and inducement mechanisms, which we would now consider a quintessentially “Hirschmanian” perspective. And Hirschman, for his part, was not too critical of comprehensive plans: in his subsequent book, Journeys toward Progress, he underscored the usefulness of large, comprehensive plans to “smuggle” reformist policies through the legislative process. In practical terms, Hirschman’s heterodoxy appeared to be less radical than it was in theory: as Amartya Sen put it, “The ‘balanced’ and the ‘unbalanced’ growth doctrines have a considerable amount of common ground.”45

The time for big theoretical debates was soon over anyway, and Hirschman was among the first to feel the need for new development thinking. Several years of foreign aid had not generated a clear understanding of what worked and what did not, and big theories clearly had not fulfilled their promises. “What if the fortress of underdevelopment, just because it is so formidable, can not be conquered by frontal assault?” Hirschman wondered. “In that unfortunately quite common case,” he continued, “we need to know much more about ways in which the fortress can be surrounded, weakened by infiltration or subversion, and eventually taken by similar indirect tactics and processes.”46 That entailed studying processes of economic development in detail. Hirschman, who had always had a penchant for history, now brought historical analysis to the center of his studies. In Journeys toward Progress, published in 1963, he examined three extended case studies of policy-making and reform in Latin America. As he put it, “The essence of this volume is in the flow of the three stories.”47 InDevelopment Projects Observed, published in 1967 and dedicated to project appraisal, Hirschman presented each development project as “aunique constellation of experiences and consequences.”48

Development Projects Observed, though well received by the scholarly community, did not have influence on development aid policies. Whereas international aid organizations were trying to measure the economic return and costs of projects and embed quantitative analysis in their routines, Hirschman focused on the intrinsic uncertainty that surrounded project design and implementation, rejecting the idea of a synthetic measure of the costs and benefits of a project as naive. Both sides had a point, but Hirschman’s approach was quickly forgotten, while cost-benefit analysis thrived. The World Bank, which had commissioned Hirschman’s research, disregarded it de facto.

As much as Hirschman was disappointed by this outcome, the development field was by then entering an identity crisis. Hirschman’s beautiful prose conveys the feeling of the end:

Some twenty-five years later, that early optimism has largely evaporated, for a number of reasons. Growth, while substantial, has by no means overcome the division of the world into the rich “north” and the underdeveloped “south.” In the south itself, moreover, the fruits of growth have been divided more unevenly than had been anticipated. And there is another, often unacknowledged reason for the disenchantment: it looks increasingly as though the effort to achieve growth, whether or not successful, brings with it calamitous side effects in the political realm, from the loss of democratic liberties at the hand of authoritarian, repressive regimes to the wholesale violation of elementary human rights.49

While Hirschman was writing these lines, others were mourning the death of development economics. Despite all their contrasts, the first generation of development economists shared the idea that less developed countries were structurally different from advanced countries; they therefore believed that the economics discipline, historically focused on advanced countries, should be significantly recast to address the problem of less developed countries. Hirschman called this idea the principle of the rejection of monoeconomics. This implied that the field of development economics was meant to be structurally different from mainstream economics.

Today the disciplinary identity of development economics is much weaker. Dani Rodrik, a leading development economist, significantly titled his 2007 book One Economics, Many Recipes, remarking in the introductory pages: “This book is strictly grounded in neoclassic economic analysis.”50 Clearly, today there seems to be no need for a disciplinary economics subfield focused on development issues and structurally independent from orthodox economics. Ironically, for his book Rodrik received the Albert Hirschman Prize by the Social Science Research Council. Yet it would be a mistake to insist on the opposition between Hirschman’s and Rodrik’s perspectives, for if they expressed different ideas on whether development economics should exist as a separate disciplinary field, they showed remarkable affinities on important methodological questions.

The disappearance of development economics as a discipline caused the emergence of eclectic approaches, in fact helping certain Hirschmanian themes filter through today’s development studies. This is why—contrary to the fate of development economics—Hirschman’s development thinking has maintained its relevance. Rodrik underscores that development studies are increasingly focusing on detailed studies of what works and what does not, disregarding comprehensive explanations. Furthermore, he highlights the importance of context-specific analysis and the focus on the bottlenecks and constraints that inhibit growth in specific situations. On the policy side, Rodrik is suspicious of “best-practices” or universal remedies and emphasizes instead selective, relatively narrowly targeted reforms. Finally, a basic hypothesis of current development studies is that there exists “lots of ‘slack’ in poor countries.”51 This suggestion is also reminiscent of Hirschman’s analyses.

Albert Hirschman was never afraid of being in a minority. He took heterodox positions toward mainstream economics, and when development economics developed its own orthodoxy, Hirschman was heterodox among the heterodox. This intellectual freedom and propensity to subversion and “self-subversion” are important elements in understanding why Hirschman’s legacy remains alive and influential.52

Notes

- In fall 2011, the Heyman Center for the Humanities at Columbia University, with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, inaugurated a long-term program on the history of disciplines. The short essays below are edited versions of the talks presented at a round table on December 10, 2013, on the first anniversary of Albert Hirschman’s death, as part of this program.

- Fernand Braudel, “Géohistoire: La société, l’espace et le temps,” in Fernand Braudel, Les ambitions de l’histoire, ed. Roselyne de Ayala and Paule Braudel (1941–44; repr., Paris: Éditions de Fallois, 1997), 104. Albert O. Hirschman, A Propensity for Self-Subversion (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- In the words of Ursula Hirschmann, Albert’s sister, as cited by Nadia Urbinati in her essay below.

- Albert O. Hirschman, The Strategy of Economic Development (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1958); Albert O. Hirschman, Journeys toward Progress: Studies of Economic Policy-Making in Latin America (New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1963); Albert O. Hirschman, Development Projects Observed, new ed., foreword by Cass Sunstein, afterword by Michele Alacevich (1967; Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2015).

- Jeremy Adelman, Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013), 12.

- Ibid., 8.

- Ursula Hirschmann, Noi senzapatria (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1993), 72.

- Adelman, Worldly Philosopher, 87.

- Ursula and Eugenio Colorni had three daughters, Silvia, Renata, and Eva; Eva was the wife of the economist Amartya Sen from 1978 until her death in 1985. I have written about the ideas inspiring the movement Giustizia e Libertà in “Another Socialism,” the introductory essay of the first English edition of Carlo Rosselli,Liberal Socialism, trans. William McCuaig (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004). Albert was, along with Isaiah Berlin, indispensable in making possible the English translation of Rosselli’s work, a seminal document of the twentieth century’s European democratic thought.

- A scholar of German philosophy specializing in Leibniz, Colorni and Ursula lived in Trieste after their marriage, and Albert spent some months with them. Colorni was imprisoned by the Fascists in 1938 and then confined on Ventotene, a tiny Mediterranean island, from which he escaped in 1943 to join the Resistance; he was murdered by Fascists in Rome in May 1944. Among the other prisoners confined in Ventotene were Ernesto Rossi and Altiero Spinelli, who coauthored in 1941 theVentotene Manifesto “for a free and united Europe,” the spiritual charter of the European Union. Ursula managed to smuggle the manifesto to the mainland and contributed greatly to its diffusion. Along with Altiero Spinelli (Ursula’s second husband), she participated in the foundation of the European Federalist Movement in 1943 in Milan and in 1975 founded in Brussels the movement “Femmes pour l’Europe.” Ursula died in Rome on January 8, 1991.

- “One day, Otto Albert asked point blank about his father’s convictions, and when Carl concluded that he had no guiding principles, Otto Albert bolted down the hall exclaiming to his sister ‘Weiss Du was? Vati hat keine Weltanschauung! (You know what? Daddy has no world view!),’ “ Adelman, Worldly Philosopher, 41.

- Ibid., 115.

- Hirschman, A Propensity to Self-Subversion, 5.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Opinionated Opinions and Democracy” (originally published in 1989), in A Propensity to Self-Subversion, 80.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Social Conflicts as Pillars of Democratic Market Society,” Political Theory 22, no. 2 (May 1994): 206.

- Cited in Diego Gambetta, “ ‘Claro!’ An Essay on Discursive Machismo,” in Deliberative Democracy, ed. Jon Elster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 20.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Doubt and Antifascist Action in Italy, 1936–1938” (talk given in Turin, in 1987), in A Propensity to Self-Subversion, 119.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Rival Interpretations of Market Society: Civilizing, Destructive, or Feeble?,” Journal of Economic Literature 20, no. 4 (December 1982): 1463–84.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Against Parsimony: Three Easy Ways of Complicating Some Categories of Economic Discourse,” American Economic Review 74, no. 2 (May 1984): 89–96. The two essays were collected in Albert O. Hirschman, Rival Views of Market Society and Other Recent Essays (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press), 1986.

- Hirschman, “Against Parsimony,” 89.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 95.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hirschman, “Rival Interpretations of Market Society,” 1464.

- Ibid., 1482.

- Ibid., 1480–81.

- Ibid., 1481.

- Ibid., 1481–82.

- Ibid., 1482.

- Ibid., 1483.

- Ibid., 1483.

- James S. Duesenberry, Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949); Ragnar Nurkse, Problems of Capital Formation in Underdeveloped Countries (Oxford: Blackwell, 1953).

- Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970); Hirschman, Rival Views of Market Society.

- Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979); Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977).

- Hirschman, “Preface to the Paperback Edition,” in Rival Views of Market Society, vi. 37.

- Albert O. Hirschman, The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism before Its Triumph (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977).

- Hirschman, The Strategy of Economic Development; Albert O. Hirschman, The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Hirschman, Development Projects Observed (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1967).

- Cass R. Sunstein, “An Original Thinker of Our Time,” New York Review of Books, May 23, 2013. Albert O. Hirschman, Shifting Involvements: Private Interest and Pubic Action (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982).

- Albert O. Hirschman, “A Dissenter’s Confession: ‘The Strategy of Economic Development’ Revisited,” in Pioneers in Development, ed. Gerald M. Meier and Dudley Seers (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 88.

- Lauchlin B. Currie, “Some Prerequisites for Success of the Point Four Program,” Address before the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, Bellevue Stratford Hotel, Philadelphia, Pa., April 15, 1950, mimeo, published in Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 270 (July 1950): 102–9.

- Hirschman, The Strategy of Economic Development, 51–52 (emphasis in the original).

- Ibid., 5.

- Amartya K. Sen, review of The Strategy of Economic Development, by A. O. Hirschman; The Struggle for a Higher Standard of Living: The Problems of the Underdeveloped Countries, by W. Brand; and Public Enterprise and Economic Development, by A. H. Hanson, Economic Journal 70 (September 1960): 591–92.

- Albert O. Hirschman, “Foreword,” in Judith Tendler, Electric Power in Brazil: Entrepreneurship in the Public Sector (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968).

- Hirschman, Journeys toward Progress, 1.

- Hirschman, Development Projects Observed, new ed., 172 (emphasis in the original).

- Albert O. Hirschman, “The Turn to Authoritarianism in Latin America and the Search for Its Economic Determinants” (1979), in Albert O. Hirschman, Essays in Trespassing: Economics to Politics and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 98–135.

- Dani Rodrik, One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007), 3.

- Dani Rodrik, “The New Development Economics: We Shall Experiment, but How Shall We Learn?” (mimeo, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, revised draft, May 21, 2008), 28.

- Hirschman, A Propensity for Self-Subversion.