Majdal Shams has long been a heartbreaking place. Since June 1967, when Israel launched its blitz on the Golan Heights as part of the shock-and-awe campaign of the Six Days War, the village has been split in two. During the Naksa, thousands of local civilians were pushed north by the invading Israeli soldiers; the remainder steadfastly remained. As a consequence, today half of the community live, displaced, under unchallenged Syrian sovereignty, north of the 1967 ceasefire line; the other half of the community live just south of that line in Israeli–occupied Syrian territory. The forcible displacement of Syrian citizens that produced this separation has been described as the “largest ethnic cleansing in history since the end of World War II”, as measured by the density of people forced to leave in relation to the geographical area targeted. The pre-war population of 142,000, living across 340 villages and farms, was reduced to 6,011 individuals, with only five villages permitted to remain. Of these five surviving villages that avoided depopulation and demolition, Majdal Shams was – and remains – the largest.[1] If the ethnic cleansing of the Golan Heights thus constituted a kind of concentrated Nakba, enacted with greater efficiency and speed than its predecessor and template, Majdal Shams is the most visible symbol of this displacement.

For decades following 1967, the personal cost of this painful separation was performed in a highly charged ritual that took place on days of communal significance. Under the watchful eye of the United Nations’ peacekeeping forces, the separated community would gather on elevated platforms on opposite sides of the ceasefire line and attempt to communicate across the gorge below through loudspeakers.[2] On the southern side of the valley, known as “Shouting Hill”, the community would call – “How are you? What news do you have? Tell me about Uncle Fadi,” and so on. On the other side of the valley, the displaced members of the community would volley their replies and counter-questions back across the valley. The distance between the two platforms and the notoriously bracing winds of the Golan compounded the difficulty of communication. On the gusty day I chanced upon witnessing this scene twenty years ago, each time the wind picked up, the voices, already crackled by the loudspeaker, would be carried away into the void of the valley, dissipating in the no-man’s-land below.[3]

The aching performance of separation at Shouting Hill expressed, on one level, the universal modern story of the border: the border that proclaims, through barely repressed violence, the spatial limits of the state; that hints always at histories of enforced separation and uprooting; and that necessarily entails the investment of extraordinary resources in its maintenance over time. Yet such inherent, structural features of the modern border are, in the case of the Occupied Golan, compounded by the naked land theft entailed: this border is not even a border, strictly speaking, in the sense of an internationally recognised line of interstate demarcation. It is a ceasefire line masquerading as a border. It is a provocation, an assertion of might that seeks to accumulate de facto legitimacy with every passing year.

Majdal Shams, this “border town” malgré lui, was skyrocketed into the international spotlight, quite literally, when rocket shards fell from the sky on the 27th of July and struck a soccer field, killing twelve children. Israel was quick to charge the militant Lebanese group Hezbollah with responsibility for the attack, a claim that was repeated uncritically in much of the international media. However, this accusation was forcefully denied by the group itself and discounted by the Lebanese Government.[4] From a tactical point of view, it seemed highly improbable that the group would have intentionallyundertaken such an attack on civilians who continue to identify as Syrian. Hezbollah has long had close ties with the Syrian government, with whom the movement has had a kind of longstanding quid pro quo: despite initially being at counter purposes during the early 1980s, when Hezbollah had been founded in the context of the Lebanese civil war, Syria subsequently helped arm the group and assured its ascendancy among the country’s paramilitary forces in the period between the Ta’if accords and the Syrian army’s eventual withdrawal from Lebanon (1989–2006).[5] Hezbollah, in turn, came to the aid of the Syrian Government during its period of crisis in the Syrian Revolution (early 2010s), becoming in effect an auxiliary for the embattled state forces. Applying the principle of Cui Bono [who benefits?], the notion that Hezbollah would have deliberated targeted the Golani Syrian civilians seems entirely counter to its wider strategic interest.

Another possible explanation for the incident at Majdal Shams was advanced by a reporter from the news network Al–Araby who visited the area in the days following and spoke with eyewitnesses, including a first responder from the Israeli ambulance service that attended the scene. This alternate account was that the rocket debris that struck Majdal Shams were not launched by Hezbollah but were rather from Israeli interceptor missiles that had veered off course.[6] The “Iron Dome”, a name which suggests an impenetrable shield in the sky, is a misleading piece of imagery: Israel’s air defences are in fact maintained via interceptor missiles shot into the sky towards incoming projectiles, in theory exploding the incoming missile, or drone, upon impact. But it is not a foolproof system. Barely two weeks after the incident in Majdal Shams, an ‘errant’ missile struck a rehabilitation facility in the Galilee, causing major damage but no loss of life.[7] It is entirely conceivable that the Majdal Shams incident could have been an equivalent scenario.

It is unlikely that we will come to know, with any certainty, the truth about the cause of the Majdal Shams incident. When Associated Press reporters visited the town in the days following the deaths, the evidence from the site had been removed and could not be independently verified.[8] UNIFIL, the United Nations peacekeeping forces stationed in Lebanon, declared that they were unable to pronounce with certainty who was responsible for the “tragic incident” in Majdal Shams.[9] Local residents have called for an independent international committee to investigate the rocket shell strike in order to “determine the party responsible, uncover the truth, and achieve justice for the victims and their families”.[10]While the lines of responsibility for the deadly incident remained obscured, what is possible to observe, with increasing clarity, is the extent to which the village’s victims could be instrumentalised within the morbid evolution of the post-October war.

Shortly after the news emerged, Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant referred to those who died in Majdal Shams as “our children”. This was calculated speech. For children have been semiotically pivotal to the moral economy of the carnage of the past year. The initial garnering of unbridled support for Israel among its allies was bolstered by the shocking story that Hamas had “beheaded babies” in the course of “Operation Deluge”, the surprise attack on October 7, 2023, that breached both the “Iron Dome” and the “Iron Wall”.[11] These stories were later revealed to have been fabricated. But the damage they intended was already delivered: such stories mentally reinforced the hard-edged binary between Israel’s self-perception as a “civilised” country in the club of global modernity, and the Palestinians as pre-modern, or anti-modern. Theodor Herzl’s vision of Israel as a “rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism” has always structured the colonial encounter in Palestine.[12] It was in this spirit that the self-same Gallant infamously described the entire population of Gaza – children included – as “human animals” and swore to “break apart one neighbourhood after another in Gaza”.[13] When Israel unleashed its unholy assault on the population of Gaza, as promised and premeditated, one of the first images broadcast to the wider world was of a distraught father holding the remains of his son in a plastic bag.

In such a context of dehumanization, for Gallant to refer to the victim of Majdal Shams as “our children” underscored the politics of differential grief, of the framing of more or less “grievable lives”, even among the indigenous Arab communities living under different shades of Israeli occupation.[14] This raw calculus of a shifting scale in human life – or what Eyal Weizman has referred to as an “exchange rate” governing the value of bodies, dead or alive, exchanged across the frontlines of the Occupation’s forever-war – has, since October 7, 2023, tilted ever more towards both uncountability and unaccountability in the taking of Palestinian civilian life.[15] As if to make this uneven reckoning of the dead more apparent, there was a grim synchronicity of the Majdal Shams incident coming a week after the Lancet Report on counting the dead in Gaza, which demonstrated the very plausible, radical undercounting of mortality under the rubble of Gaza.[16]

The attempt to render the dead children of Majdal Shams more calculable, grievable and knowable than their Gazan counterparts, has a much longer genealogy. For decades, successive Israeli governments have tried to bring the Syrian Druzes of the Occupied Golan into the orbit of the special relationship that is often claimed to exist between the Palestinian Druzes and the State of Israel, referred to as the “covenant of blood”, or “treaty of blood”. The roots of this alliance reach back into the dying days of Mandate Palestine, when members of the community who surrendered to advancing Irgun troops during the 1948 war were spared the ethnic cleansing operations of the Nakba and permitted to remain in their villages, concentrated in the Galilee.[17] Between 1956 and 1957, this pact was formalised and contracted upon the expectation of military service to the State of Israel in exchange for preferential treatment within the “ethnocracy” of the state.[18] However, behind the celebratory narrative of a Jewish–Druze partnership is a much more complex history of Druze protest against enforced conscription and Israeli containment of the ongoing presence of the community in the officially Jewish state.[19]

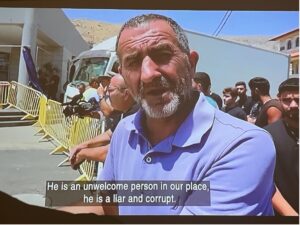

Despite decades of such efforts of enticement by Israel, the majority of the Golani Druzes remain fiercely loyal to Syria. The Golani Druze are revered in the historiography of Syrian nationalism for their proclivity to take part in uprisings against abuses of state power. In the late nineteenth century, they were central to the periodic revolts against what Ussama Makdisi memorably called “Ottoman Orientalism”: the over-extensions of the reformist state pushing modernisation projects into the putatively “backward” rural Arab provinces.[20] A generation later, when communities within the newly enclosed French Mandate over Syria rose up against colonial domination, it was the Druze who were at the forefront of the rebellion. Sultan Al-Atrash, the legendary leader of the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927) hailed from this region and remains a local folk hero: in the centre of Majdal Shams, a statue of his likeness on horseback going into battle occupies a prominent place in the town square. Despite numerous overtures since Israel formally annexed the Golan in 1981, the majority of Golani Druzes have continued to refuse Israeli citizenship, preferring to remain Syrian subjects.[21] The hostile reception that Netanyahu received in Majdal Shams when he arrived for his propagandistic photo opportunity was testament to the failure to incorporate these residents into the associational fold of Israeli identity. The Far-Right finance minister Bezalel Smotrich was chased out of town the previous day for having the hutzpah to appear at the funeral and try to extract political capital from the grief. Netanyahu himself was denounced by protesting residents as a war criminal, a corrupt and compulsive liar who was not welcome in the town.[22]

Screenshot from SBS World News, Australia, evening broadcast from 31 July 2024.

The raw, unmediated grief at Majdal Shams – a grief that resisted cynical attempts at its appropriation – triggered a momentary resurfacing of repressed history. As in other parts of the post-October conflagration, the anguish of victims’ families cast a light on the various regimes of Israeli occupation applying between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, and from the edge of Sinai Desert in Gaza to here, in the foothills of Mount Hermon. The unassimilable despair of the victims in this oft-forgotten corner of occupation cut through the long since tacitly legitimised status quo. The Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong came under significant criticism for referring to Majdal Shams as a “northern Israeli town”. Her lapsus linguae suggested, critics feared, either a concerning lack of knowledge of the region or a tacit normalisation of this forgotten occupation.[23] Given that, at the time of writing, Wong has made no effort to correct her tweet, the apparent, undeclared shift in official Australian policy on the Golan would seem to indicate a quiet falling into line with US official policy, which since March 2019 has recognised Israeli sovereignty over the annexed territory.[24]

The return of historical consciousness on the question of Israel’s post-1967 occupations had exploded like its own kind of rocket a week before the unclaimed blow on Majdal Shams. The International Court of Justice issued its Advisory Opinion on 19 July 2024, re-affirming the lapsed responsibility of states – including states like Australia – to observe the illegality of occupation of the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967.[25] Among the judges on the bench of the ICJ, Judge Hilary Charlesworth, herself an Australian jurist, noted that “the intensity, the territorial scope and the temporal scope of Israel’s policies and practices undermine the proposition that Israel’s occupation qualifies as an act of self-defence”. Charlesworth used her declaration to highlight “the existence of discrimination on multiple and potentially intersecting grounds, including gender and age”.[26] In other words: the occupation has a specifically discriminatory effect on children, and on girls in particular.

From the vantage point of late October, as I write these closing lines, the Majdal Shams incident has come into sharper relief as a moment of morbid evolution in the shape of Israel’s assaults on its opponents. In the days immediately following, members of the community issued a public statement, declaring that they did not want the blood of their children to be exploited as a guise for attacking any other Arab state.[27] Observers of the incident from the Druze diaspora likewise expressed concern that “the tragic death of children [could] be used for political capital by Israeli leadership or justification for any retaliatory attacks on Lebanon.”[28] These statements were prescient, for this is precisely what has happened since. The incident fell into the lap of the Far-Right elements in the Israeli Government who had been itching for months to expand the war with Hezbollah. It was seized upon as a pretext for the assassination of senior Hezbollah military official, Fuad Shukr, in Beirut. Ismail Haniyeh, the political leader of Hamas, was assassinated in Tehran a day later.

Yet even this was not the end of the escalation. Two weeks later, Israel inflicted twin terror attacks on Lebanon: the first on the 18th of September involving the explosion of pager devices used by Hezbollah operatives; the second the following day aimed at walkie talkies used by the group. This weaponisation of telecommunications was sold to the world as a “targeted” move against militants, and received in some quarters as “sophisticated”, “stunning” or a “masterstroke”.[29] A kind of cynical realpolitik, entirely unmoored from the normative framework of international law, dismissed the legality or otherwise of the attacks, focused instead on the detail of their planning and execution.[30] Given that the coordinated explosions were timed for a moment when the militants were out in the general public, they were clearly designed for maximal collateral civilian maiming. And then, with barely time to digest the horror of these attacks, and their implications for the safety of Lebanese citizenry, came more intensification. The subsequent aerial bombardment campaign against Lebanon and the assassination of Hasan Nasrallah proffered evidence of a “long-prepared and multi-pronged effort to decapitate Hezbollah”.[31]

In this unbridled expansion of carnage, the retrospective knowledge of what has latterly transpired puts the mediatic manipulation of Majdal Shams in a different light. The prosecution of the war in Lebanon is increasingly resembling the same model of urbicide, or total war, that rolls on, incessantly, in Gaza: directed towards the collective punishment of whole populations and the rendering of functional civilian life impossible.[32] Amidst the escalation, almost imperceptibly, the narrative drip-fed by the IDF to the world media shifted: no longer was it matter of divine vengeance for dead children on a soccer field in the Golan; or even for the original victims of October 7. Now, the justification for the wholesale destruction of Lebanon was for displaced families from the north of Israel the ability to return to their homes. As I write this, Iran has just been struck once more, and – the media tells us – we stand once more with the very real possibility that we find ourselves on the precipice of a larger, regional war. What work do these narratives do? The opening of so many new fronts in this process of regionalisation has not only made the live-streamed genocide of Gaza a “mere sidenote,”[33] it has dazed and confused the attention of the global news-consuming public, dulling the capacity for protest, generalizing the feeling of despair.

What does it mean to bear witness to all this? When the time comes to write the history of this war without limits, how will particular inflection points like Majdal Shams be remembered and interpreted? It seems reasonable to suggest that the capacity for which the loss of life has captured, or failed to capture, the empathy of the international news-consuming public will be an important vector for making sense of the silence and complicity of so many governments, my own included. In the framing of the lives lost as Israeli, or almost Israeli, the Majdal Shams incident gave this Arabic-speaking community a passing purchase on grievability, and their humanity a momentary legibility. That this community remained subjects of occupation insisting for their deaths not to be instrumentalised was a minor but not insignificant act of resistance to the manipulation of death and the parcelling out of selective humanity.

The incomparable Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who witnessed the horrors of the Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982, entitled his prose-poem memoir of this period Memory for Forgetfulness. The task of the poet in such times, he insisted, was not only to bear witness but also to preserve memory against the ravages of forgetfulness, that human capacity towards amnesia in the face of unspeakable tragedy. The poet’s recollection thus became “an act of memory, a monument, against forgetfulness and the ravages of history”.[34] The task today is analogous: against the erasure of the value of human life we must continue to chronicle against forgetfulness, and to insist on the value of the life lost.

[1] Nazeh Brik, “Syrian residential communities destroyed by Israel after occupying the Golan in 1967,” Majdal Shams: Al-Marsad Publications, 2022, as cited by Maria Kastrinou, “From the Golan to Gaza: Ethnic cleansing and the colonial logic of Israeli occupation,” Syrian Studies Association Bulletin 28:1 (Summer 2024), 14.

[2] “Occupied Golan: stories of separation,” International Committee of the Red Cross, 5 June 2007, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20230303134743/https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/feature/2007/israel-stories-050607.htm

[3] The frequency of this ritual has reportedly subsided over the past decade, as the increased prevalence of mobile phones has changed the modality of communications for the separated community.

[4] “Speaker Berri confirms the resistance’s non-involvement in Majdal Shams incident,” LBC International, 28 July 2024.

[5] In 1990, when the Lebanese civil war gave way to a period of de facto Syrian occupation of Lebanon, Hezbollah alone among the militias was permitted to retain its arms.

[6] “Golan Heights attack: The claims and counterclaims on Majdal Shams strike,” Middle East Eye, 29 July 2024.

[7] Susan Dirgham, “Majdal Shams: lies, law and war,” Pearls and Irritations, August 23, 2024. Gavriel Fiske, “War-wrecked Galilee center for kids with disabilities plans to be ‘larger and stronger’,” Times of Israel, 15 August 2024.

[8] “A cratered field, a mangled fence. Clues emerge from strike that killed 12 children in Golan Heights,” The Washington Post, 30 July 2024.

[9] “UNIFIL unable to ‘attribute responsibility’ for Majdal Shams massacre,” The Cradle, August 2, 2024.

[10] “Al-Marsad calls for an international committee to investigate the rocket shell strike on a football field in Majdal Shams in the occupied Golan,” Press Release, August 7, 2024, available at https://golan-marsad.org/al-marsad-calls-for-an-international-committee-to-investigate-the-rocket-shell-strike-on-a-football-field-in-majdal-shams-in-the-occupied-golan/

[11] These twin metallurgical metaphors have long animated Zionism’s relationship to its geography. For the original conception of the “Iron Wall” see Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, “The Iron Wall,” originally published in Russian on 4 November 1923.

[12] Stephen Pascoe, Virginie Rey and Paul James, “Introduction: Making Modernity from the Mashriq to the Maghreb,” Arena Journal 4 (2015): 1–13. Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (New York: Dover, 1988), 96.

[13] Omer Bartov, “As a former IDF soldier and historian of genocide, I was deeply disturbed by my recent visit to Israel,” The Guardian, 13 August 2024.

[14] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2010).

[15] Eyal Weizman, “Exchange Rate,” London Review of Books, vol. 45, no. 21, 2 November 2023.

[16] Rasha Khatib, Martin McKee and Salim Yusuf, “Counting the dead in Gaza: difficult but essential,” The Lancet, Volume 404, Issue 10449, July 20, 2024.

[17] Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld Press, 2006), 55, 109, 114–115. See also Laila Parsons, “The Druze and the Birth of Israel,” in Eugene Rogan and Avi Shlaim (eds.), The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 60–78.

[18] Oren Yiftachel, “Democracy or Ethnocracy?” Middle East Report 207 (Summer 1998).

[19] Yusri Khaizran, “The Druze in Israel: Between Protest and Containment,” Jerusalem Quarterly 96 (2023): 8–27.

[20] Ussama Makdisi, “Ottoman Orientalism,” The American Historical Review 107:3 (June 2002): 768–796.

[21] Kastrinou, “From the Golan to Gaza.”

[22] “Angry Syrian Druze residents confront Benjamin Netanyahu at Majdal Shams during his visit,” The New Arab, 30 July 2024.

[23] Daniel Hurst, “Australian government scrambles to clarify stance on Golan Heights after Wong references ‘Israeli town’,” The Guardian, 31 July 2024.

[24] This is consistent with Australia’s sub-imperial position in relation to US hegemony. As Clinton Fernandes has argued, “Australia supports Israel regardless of its conduct, but not because it has been manipulated by a domestic ethnic lobby. No lobby group in Australia can dominate foreign policy or acquire influence in the mainstream media for very long unless its goals are aligned with the broader interests of Australian capitalism. The so-called Israeli Lobby has not hijacked Australian foreign policy but operates in harmony with it. There is a strategic convergence between its aims and the ‘national interest’ of upholding the US-led imperial order.” Clinton Fernandes, Sub-Imperial Power: Australia in the International Arena (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2022), 54.

[25] “An open letter from legal experts on the ICJ Advisory Opinion,” Overland, 22 August 2024. https://overland.org.au/2024/08/an-open-letter-from-legal-experts-on-the-icj-advisory-opinion/

[26] Summary of the Advisory Opinion of 19 July 2024, Case 186 – Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, including East Jerusalem, International Court of Justice. (The scope of the court’s investigation was limited to Palestinian territories and did not specifically address the legality of Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights.)

[27] Najwan Berekdar (@NajwarBer), “#Israel is “responding” by attacking Beirut while exploiting the death of children in the occupied Syrian Golan,” X, July 31, 2024, 6:20AM, https://x.com/najwanber/status/1818381156342956490?s=42

[28] Nathin Klabin, “American Druze Community Fearful Majdal Shams Attack Will Be Used To Justify More Violence,” The Media Line, 5 August 2024. https://themedialine.org/by-region/american-druze-community-fearful-majdal-shams-attack-will-be-used-to-justify-more-violence/

[29] For an example of this kind of reporting, see Mathew Knott, “Ex-Mossad and CIA agents astounded at sophistication of pager attack,” The Sydney Morning Herald, September 20, 2024. For an astute critique of such reporting, see Jan Fran, “Of course journalists described Israel’s possible war crime as a the stuff of sexy spy thrillers,” Crikey, September 27, 2024.

[30] One such account declared that the legality of the attack was “mainly of academic interest”. Rodger Shanahan, “Why did Israel choose 3.30pm on a weekday to detonate its explosive pagers?” The Age, September 19, 2024.

[31] Peter Beaumont, “Israel’s strike on Hezbollah is an alarming escalation in conflict,” The Guardian, 28 September 2024. See also Dan Sabbagh, Lili Bayer and Dan Milmo, “Pager and walkie-talkie attacks on Hezbollah were audacious and carefully planned,” The Guardian, 19 September 2024.

[32] Stephen Pascoe, “The Ghosts of 1982,” Pearls and Irritations, October 20, 2024.

[33] Rachel Coghlan, “‘We had to run for our lives’: 86% of Gaza is now under forced evacuation orders,” Crikey, 6 August 2024.

[34] Ibrahim Muhawi, “Introduction,” in Mahmoud Darwish, Memory for Forgetfulness: August, Beirut, 1982 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), xix.