In literary studies, questions of race, power, and terror raised by the mention of the Zong atrocity have long been familiar. While the facts of the case are well known—in 1781, a captain of a British slave ship chose to throw 133 slaves overboard so that he could claim them as insurance losses—the afterlife of Zong far exceeds its eighteenth-century abolitionist frame of moral outrage, legal maneuver, and humanitarian activism. Following in and amplifying J. M. W. Turner’s footsteps (whose 1840 painting Slave Ship galvanized sentiment against slavery), numerous poets, novelists, artists, and historians have turned to the still unfolding implications of this horrific event and the subsequent legal battle to make the very name Zong an iconic one for studies of slavery, race, and blackness, as well as for our conceptions of history and racial capitalism. For Ian Baucom, the Zong atrocity names not an isolated or exceptional incident—rather it emblematizes the very logic at the core of contemporary financial systems and human rights regimes, the heart of what we inhabit as Atlantic modernity.1 For Paul Gilroy, an understanding of a black Atlantic counterculture of modernity rests in a similar refusal to see the past as settled and to mine contemporary culture for coded and potentially transformative visions of justice derived from slavery, particularly from the chronotope of the ship.2 Recently, Christina Sharpe connects these meditations on the slave ship to contemporary black life in “the wake” where African migrants to the Mediterranean and Europe “are imagined as insects, swarms, vectors of disease” and “the semiotics of the slave ship continue: from the forced movements of the enslaved to the forced movements of the migrant and refugee.”3

Current Issue

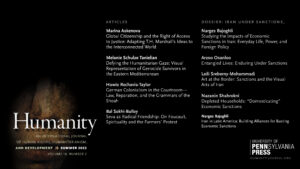

Our long-awaited issue of Humanity journal is out! Its special dossier, Iran under Sanctions, examines the myriad and devastating impacts of international sanctions on society, culture, and politics. The issue includes an essay on the legal case Herero and Nama v. The Federal Republic of Germany to theorize reparations for German colonialism and slavery as they became linked with the aftermath of the Shoah. It also includes essays on T.H. Marshall and the right of access to justice; visual representations of Armenian genocide survivors; and, the concept of radical friendship in relation to the Farmers’ Protests in India.

View entire issue > Save Save Save

📘'Choose Your Bearing: Édouard Glissant, Human Rights and Decolonial Ethics' is now available for pre-order!

❕Grab your copy and save 30% OFF using the code NEW30 at checkout : https://edin.ac/3JIcRne

@HumanityJ