Humanity: How did you decide to cover the invasion of Iraq from the Iraqi side? How did this relate to your experience as a journalist?

Kael Alford: By 2003, I had been covering countries in conflict on and off for about seven years. For most of that time I was living in the Balkans, not jumping from one region to another but digging down deep, seeing a continuum of events. I covered the invasion of Kosovo by NATO troops, lived in Serbia under the last days of Milosevic, and had recently made a trip to Palestine and Israel during the IDF’s incursion into Jenin. Those experiences were fresh in my mind when I imagined U.S. troops invading Iraq. I suspected that the American-led war would not be as simple as the U.S. administration was making it sound. I thought that the presence of American soldiers in Iraq could easily bring about a backlash from Iraqis and throughout the region. It struck me as strange at a time when radical Islamists were using the U.S. presence on Muslim soil as a justification for terrorist attacks, that the U.S. was planning to launch a new invasion that would provide such easy fodder for that rhetoric.

I thought the war was going to have a whole host of unintended consequences. Anyone who covers modern conflict knows that civilians bear the brunt of the majority of violence and I suspected the war in Iraq would not be an exception.

These dangers seemed evident to me as a casual observer. Yet the decision makers in Washington, whose advisors were certainly more experienced than I in warfare, Middle East politics, and foreign policy, would go ahead with the plan to invade despite the obvious dangers.

I wanted to be on the ground in Iraq during the air campaign and the invasion to document events as they unfolded to test the pre-scripted narratives and intentions of the U.S. from a civilian perspective, rather than embedded with U.S. troops. I thought that among Iraqi civilians, the immediate consequences of the war for Iraqis would be most evident.

H: The Iraq war has certainly blurred the distinction between reporting and waging war, turning information into a strategic weapon. It also triggered the beginning of “embeddedness” as a new military practice of control, first with journalists, but now extended to civilian researchers such as anthropologists. Can you tell us how the “unembedded” project was conceived?

KA: I was aware of the history that led to the embedded journalism program of the U.S. military through my training as a journalist. But it’s nothing new for governments to use information and the media to influence perceptions or to gain the upper hand or popular support. We journalists must be vigilant if we want our reporting to stand independent of the powerful sway of wartime propaganda. Recent psychological operations by the U.S. military involve an array of information and disinformation campaigns.1 Planting news stories in Iraqi media, spraying graffiti messages on walls in Arabic, offering misleading information to domestic journalists were all tactics employed by the administration and by the military.

During the lead-up to the war in Iraq, much of the American media failed to ask the most difficult questions or challenge the justifications for war thoroughly enough, but the tactics employed by officials were nothing new.

During World War II, many American journalists saw it as their duty to support the American war effort outright. The perception that mass media can challenge official information on the battlefield in wartime is really something that has evolved along with the mass media and it wasn’t until Vietnam that the media had unfettered access to the battlefield. Even during the Vietnam War it took years for the dominant media narrative to depart significantly from the official reports coming from Washington.

The precedent to the embedded journalism program started during the Persian Gulf War in 1991 when small press pools were allowed to accompany military units. It was the U.S. military’s attempt to gain more favorable coverage of their operations and control access to information—a reaction on the part of the military to apply some lessons learned during Vietnam War–era coverage. There was less access to troops and there were greater restrictions on the media during the press pools of the first Gulf War in 1991.2 The embedded program during the 2003 invasion allowed a larger number of journalists more intimate access to U.S. troops, and was a response to journalists who wanted to have more access than allowed in 1991. Studies, however, have suggested that reports from embedded journalists do provide more positive coverage of the war than reports from journalists who do not travel with troops.3

Among the handful of journalists who were in Baghdad in 1991 during the first Gulf War, at least one was imprisoned by the Iraqi government and others were criticized at home in the U.S. for reporting too sympathetically from Baghdad.4 That helps to explain some of the anxiety among journalists trying to cover the Iraqi side independently before the invasion in 2003. In Baghdad in 2003, journalists spoke of fears of being arrested or used by the government in some way and were likely worried about seeming like apologists for the regime.

Then the term “unembedded” began to be used loosely after the invasion to mean those who were not traveling as part of the U.S. military’s embedded journalism program. Another word used frequently to describe journalists who were traveling independent of the embedding program was “unilateral,” a term with a military ring to it. Basically it was the embed program that prompted the distinction between being with the troops officially or not, which previously didn’t exist in journalism parlance. There is a document one must sign, in order to be embedded with U.S. troops. It includes some language about images of wounded or dead troops, the point at which images can be released, and other restrictions on militarily sensitive information.5

We used “Unembedded” as the title of our book to draw attention to the trend of embedding officially with troops, and the very different physical perspective journalists gained when they were not surrounded by the military during their reporting.6 Embedding is a good way to understand the dimensions of the conflict as they related directly to the soldiers and their movements on the battlefield. It can even be a good way of learning about the contact between military and civilians. But being embedded limits your movements and social interactions with civilians, making it difficult to understand the impact of the conflict on ordinary people and on society on a wider scale. And when you’re always coming and going with soldiers, people assume you’re with them—you’re on their side—and suspect that everything you report will immediately get back to the military.

The military’s new programs involving anthropologists, sociologists, and other specialists come from a desire to influence events more effectively. After all, that’s why the U.S. military is there: not just to build schools and rebuild governments but to influence events and to make allies and kill enemies. I don’t know from firsthand experience how those civilians are working with the military; but I do know that, on the ground in Iraq or Afghanistan, anyone who travels with the military or delivers them information is seen as a part of the unit.

Even programs to rebuild infrastructure such as schools or hospitals, when they are done by Americans in uniform, or by groups seen as allies of those soldiers, often become targets of opponents. Civilians may also suspect the military has ulterior motives. And of course they do. Unlike a journalist who might be embedded for a week or a month, but is still free to leave that embed and say what they want later, the anthropologist employed by the military is just that, an employee, a much more limiting position. I’d like to see what sort of contract they’re asked to sign going into that job. It’s important to recognize there is some very good journalism done by embedded journalists, and plenty of critical or less than flattering reports are made that way. Sometimes it means a journalist is not welcome back to embedded positions in the future.

The photographers in Unembedded all met in Iraq—except for Thorne Anderson and me; we’ve worked together on and off for years. Rita, Ghaith, Thorne, and I saw each other on a regular basis in Iraq, often crossing paths as we moved around the country. We respected each other’s work and tended to focus on stories that were not accessible during embeds. It wasn’t until after we left Iraq that the idea of collaborating on an exhibit and book came about. I think we were each looking for ways to disseminate the narratives we’d witnessed, which were often on trajectories that contradicted the official or dominant view of events. I myself was frustrated with the limited ability photojournalists have [to influence] how a story is told or how their images are used. Unembedded was a way for us to tell the stories the way we saw them unfold, and gave us a framework for sharing our experiences directly. News outlets can only publish a limited number of photographs on pages crowded with local and international news. By taking control of our own project, we could describe what we’d witnessed in the most representative way. I felt I owed that to the people I met in Iraq to get the story right.

H: What was your experience with your fellow foreign photographers in Iraq?

KA: While in Iraq, I can’t say that what I was doing was terribly different from what others were doing in obvious ways. I never took an embed: that was a bit unusual. And I tended to follow events rather than rely exclusively on assignments to direct me. Working as a freelancer gives one a lot of freedom in that regard. It also comes with a lot of insecurity and a minimal amount of logistical support.

The Unembedded project grew organically out of our experiences. In the first two years of the war in particular, which is the time I was there, most American coverage glossed over a lot of the complexities, problems, and looming questions inherent in the American project in Iraq. We wanted to offer a narrative that highlighted what we thought was being underrepresented in that coverage.

For example, I tried to get as much access as possible to the resistance movements early on. There were other journalists doing that too, although not very many, particularly when the resistance movements were first getting started in 2003 and early 2004. I have often wondered whether, had the media given early resistance groups and disgruntled regions of the country more thorough coverage from the beginning, the relationship between the media and those groups might have developed a little differently. The story about various resistance movements got buried for a long time and didn’t really become news until more radical resistance elements surfaced; and by then, some Sunni groups were targeting journalists.

Just before and during the invasion, there was an unspoken attitude of support for the war among many American journalists in general. That attitude was less pronounced among non-Americans. I think the pro-war attitudes stemmed from recognition that the regime was very oppressive, and some old Iraq hands who knew the country felt that anything, even a U.S. invasion, was better than Saddam. From journalists who knew very little about Iraq or the military and parachuted into embeds came reports about the U.S. military’s experience of the war ignoring the impact on Iraq. U.S. soldiers were the kids, husbands, and wives of American readers and that was a compelling story for readers. Generally speaking, the experience of soldiers is more interesting to a lot of publications and television stations than the perspectives and experience of Iraqis. I was definitely looking to understand the war from the perspective of Iraqis, and its impact on civilians and Iraq’s social landscape, as much as possible.

H: How does the “peer group” of war photographers exert a filtering influence on what is approved or consecrated? Are there fault lines in this group?

KA: I doubt there was ever a more fractured group of professional journalists than photojournalists. Long before big newsrooms layoffs, downsizing of the print news business in the U.S., and even before the bulk of the digital news revolution, good staff photographer jobs that allowed for foreign travel were few and far between. So if you wanted to earn a living covering foreign news, you’d need to go out there and learn how to live and work in a region, and prove yourself capable to some extent. Then you’d need to meet the editors at major publications and let them know where and when you’d be in the regions where they needed photographers. That’s the case more now than ever before. Budgets for foreign news are dwindling and a shrinking number of publications are willing and able to pay for such coverage. Oddly, this is coinciding with an explosion of young photographers who want to cover news and social events around the world, including some very talented photographers in countries that previously didn’t have a strong culture or history of photojournalism.

Photojournalists do have a kind of brother- and sisterhood, but that comes from having similar experiences and living a disjointed life that few other people can understand. And there are codes of conduct certainly, that center on professionalism, ethics, and a general belief in decency toward other people, particularly the people we photograph, who are sometimes in very distressing situations. Photographers who don’t respect their subjects don’t get very far among their peers. In that way, it’s a somewhat self-regulating but loose-knit society.

As far as filtering goes, I think a lot of that happens in the newsrooms themselves—how resources are allocated, what stories staffers are assigned to cover, and what the insurance companies will allow staffers to do—are decisions made on the home desks. Among freelancers who make up the bulk of foreign photographers, many are willing to put a lot on the line to tell stories. Often they have good ideas of their own. But usually, it’s the editors and writers who decide what the story is or what the approach should be. Sometimes what an editor in New York thinks is important may not be the most compelling or newsworthy story. Photojournalists, particularly freelancers, sometimes buck this system by trying to come up with their own projects, and then look for a publication or audience who will pay attention. It’s not an easy road.

H: Embedding journalists resulted from an articulated strategy about the role and the control of public opinion in the unfolding of a conflict. Do you think the phenomenon of embeddedness (and unembeddedness) points at a more reflexive attitude than in the past toward the role of information and reporting? Did it lead you to think more than before about the perspective from which you report?

KA: The opportunity to embed with U.S. troops during the invasion paired with the difficulty of getting visas approved by the Iraqi government did funnel some journalists into the positions traveling with U.S. troops. It meant that hundreds of journalists were embedded while only a handful of U.S. journalists were in Baghdad. I knew there would be a deficit of journalists who were reporting from the capital and I worked very hard at getting an Iraqi visa. So did many other journalists. I got lucky. There were hundreds of journalists in Amman, Jordan, hoping for Iraqi visas, who came into the country after April 9, when the Marines reached the center of the capital.

After the invasion, it became much easier for journalists to get access to the country without the help of troops. Ideally, embedding or not embedding is a choice that journalists make depending on the particular issue they are trying to report. Until recently, many American news bureaus kept offices in Baghdad and reported from the city on a daily basis; but whether or not they were reporting much about average Iraqis is another question. I think that the general public doesn’t really understand the physical logistics of news reporting from Iraq, and the terms “embedded” or “unembedded” have come to mean something more like bias or lack of bias, complicity with the official agenda or a departure from it. Rarely, however, is the situation ever so black and white. People need to read more deeply.

Journalists can certainly be embedded and still engage in reporting that is critical of what they see. Some of those journalists also get booted from their embeds for reporting negatively, and in other situations commanders may support journalists who are critical of what they find.

There is something of a knee-jerk contingent out there that oversimplifies the categories of coverage. We know that during wartime news tends to slant toward supporting the official government positions. This is an old phenomenon. The adage that truth is the first casualty of war has a basis. It’s difficult to get good information during wartime because various interests have very different agendas and information is used as a weapon. It’s also difficult to get around, get access to the battlefield, sort through the suspicions and fears.

On a side note, it’s strange that more people don’t question whether or not our actions abroad can backfire and create more enemies and instability than existed before—when clearly that happened in the case of Afghanistan in the 1980s, for example. Maybe the fact that most popular mass media focuses on daily events without much historical context is partly responsible for this. I think that for Americans the biggest handicap is that war seems like a distant phenomenon and we can go about our lives without thinking about remote battles fought in our name.

H: The term itself—“unembedded”—became something of a fashionable concept and migrated in a variety of arenas, including pop culture. How do you consider this phenomenon and what does it tell us, according to you, about ourselves?

KA: The use of the term “unembedded” is popping up all over the place since the Iraq war, particularly in nontraditional news contexts. It seems to be a synonym for “independent” or “nonestablished,” in the way the word “alternative” was applied to media in the 1970s and 1980s. It has quickly become almost meaningless in some of its current uses. In the case of our book, we wanted to make it clear that the images we collected were made while not embedded with the U.S. military’s embedded journalism program. That is a particular physical perspective and it’s quite specific. We were hoping to call attention to how things look outside of troop formations—which, due simply to logistics, movement, and access, is different than what is visible while traveling with troops. Show up to someone’s village in a convoy of soldiers, and people will treat you very differently than if you arrive in a taxi, for better or for worse.

Generally speaking, though, the fact that more people are latching onto this idea of being outside of a prescribed or official perspective or program is a good thing. Audiences, I hope, are growing increasingly skeptical of information. When well applied, that skepticism can lead to more critical reading of the media and a more sophisticated understanding of how news is gathered, fact checked (or not), edited, and distributed.

Conversely, audience skepticism in its most destructive form leads to conspiracy theories and an elevation of opinion, suspicion, and ranting over carefully recorded information. There is a value in the system of checks and balances that traditional print newsrooms provide. There’s also plenty of room for improvement.

H: Your work provides a brutal counterpoint to the claims made about the humanitarian nature of the Iraq war. What is the standpoint from which you develop this vision?

KA: Even when wars are fought for morally complex and somewhat defensible reasons, they are immensely destructive. I think the United States takes war much too lightly and gives military action unwarranted credibility as a mechanism to improve security or to provide social change. Perhaps U.S. citizens collectively accept war as a reasonable way to react so easily and often because we have not had a war on our own soil in a long time. We’ve forgotten how destructive war is not only to our enemies, but also to ourselves. We’ve forgotten the legacy of anger and despair war leaves behind. Military families might understand this a bit better than most.

The United States is a nation of relatively very wealthy people on an island removed from the countries where we wage war. On average, we have a limited knowledge of the history of these other countries and a limited physical and cultural perspective based on our own experience. All of these limitations are understandable—they are simply human and circumstantial. But from our leaders, we should expect more. We should be electing leaders who speak foreign languages, who have traveled, who know history, and can act fairly on an international stage. I think if we are going to thrive in the future, we’ll need to learn to appreciate these qualities in our leaders and become more international ourselves.

The most surprising thing I’ve learned as a journalist is that even the most horrific violence has an explanation. That doesn’t mean violence becomes more defensible—it means that most human behavior is explicable. There are causes and effects of human behavior just like there are for the behavior of other creatures on the planet. Angry people become violent—frightened people too. Despair, disgrace, and lack of power can lead to violence. The list of causes of violence is long but often the causes are comprehensible. When people are violent toward us as a nation we need to care about why. As the face of warfare changes, and terrorism becomes easier to execute, we will need more knowledge of the social, economic, and political realities around the world. Our own security depends on the security of the planet. This isn’t a job for the military. This is a job for educators, leaders, and well-informed, worldly citizens who vote.

The logic underlying why the military is looking more to social scientists and anthropologists makes some sense. American soldiers are learning that local, cultural information can be useful on the battlefield, particularly during long occupations. Of course, those very experts they are hiring will be seen as accomplices to the military in the theater of war. The military is not a force of peace or diplomacy. They are there to kill enemies and leave behind a compliant country and government friendly to the home nation’s interests.

H: At some point in your work Windows on Iraq, you say that it is important for journalists “to acclimate to the communities around them” and you go on to say that you tried to dress and behave in accordance with the local customs. Would you describe this simply as a better reporting strategy, or is it something deeper, a form of self-transformative empathy? Would that point at a humanitarian concern in your work?

KA: This goes back to what I was saying earlier. Effective journalists need to understand where they are, to be respectful and humble if they want local people to trust them and be their guides through the place where they are reporting. A good journalist does not assume that a particular political course of action is correct. Instead, journalists should be questioning the wisdom of our leaders, checking on military policies in action, asking if they are effective, ethical, representing the will of the people, or in keeping with our national values. This is the role of journalists in a democracy. I think that these values are also in keeping with humanitarian concerns. I hope that most Americans want a military that behaves according to basic guidelines for human rights, for example. So if we are to be effective as journalists at understanding the impact of our actions on foreign soil, we need to gain as thorough an understanding of that place as possible. We can assume very little. We have to immerse ourselves to learn where we are, and become sensitive to the nuances of culture, politics and social structures. That’s essential to a more accurate perception of events, cause and effect. Failing to speak the local language is a huge disadvantage to a journalist. At the very least, we need collegial relationships with interpreters and trustworthy sources and to be very attentive to the environment we’re in. I would guess that some anthropologists advising the military may be telling soldiers something similar; but once again, soldiers have a different mission than journalists.

H: One of the many characteristics that distinguishes your work from mainstream war reporting is that it does not reduce its subjects to mere victims of war, whose life is reduced to a “bare life” that is only taken or saved: your photographs show active individuals who live, marry, go about their business at the same time as they fight. Is there a conscious element of reaction to the humanitarian depiction of victims as pure victims?

KA: The people of Iraq, or those in any other difficult situation, are not powerless. They may exercise their power by fighting an occupation, or voting, or boycotting an election, or blowing up a mosque or a police station; or by struggling for an education for themselves or their children; becoming a politician or an activist. All of these reactions to a difficult situation are comprehensible and have motivations and a personal backstory. Photographers should be careful that their images don’t reduce people to two-dimensional victims. Photographers should get beyond their own nationalism and assumptions well enough to see different perspectives.

Iraqi fighters, like American soldiers, have families and motivations for joining the ranks. They might just as easily be financial, political, or ideological, but if you don’t ask them, you’ll never know. It often seemed to me that the military planners were very unaware of whom they were fighting in Iraq or what their motivations were. It’s an old piece of tactical wisdom: know your enemy. Humanizing enemies in this way also makes people less frightening. War propaganda demonizes enemies, real or perceived, to make enemies appear more ruthless, less like ourselves and easier to kill. Journalists should not engage in such reductions.

It’s important for journalists to show the range of lives and experiences in a conflict zone, so that our audiences learn the complexity of the nations and cultures. Knowing the personal stories of Iraqis and the range of life and characters and beliefs gives us a more realistic view.

H: The “imaginary” of human rights and humanitarianism, so central today to war efforts and all kinds of interventions, largely relies on the power of images. How do you see yours fitting into this context?

KA: It’s true that images have the ability to stir our emotions. Through images, we can react to the situations and experiences of people who are not present. I get tired of photographs that simply shock us or stir only pity or dismay. There is a place for those images but to understand a distant situation, it’s important to see a broader view of life. I try to share the moments of relief and reprieve that I also see. These are the experiences after all that help us all stay sane in the face of tragedy. A very well-respected American Muslim scholar who often speaks on issues related to reconciliation once told me that he is concerned about the power that images have on people, that showing only violence and despair can incite violence and elevate despair. I take his point. Though I do think documents that bear witness to horror are important, even war is not only about trauma. When faced with terrible circumstances, people are also capable of courage, humor, and experience moments of relief. There is even beauty. The lives and motivations of others are just as complex as our own.

When someone puts a label like “humanitarian” on war, I am very suspicious. War comes at a high price, and even when it puts an end to one cycle of violence, it begins another.

H: Who are other crisis photographers who have influenced you, if any? Or noncrisis photographers? What are the differences in responsibility that a photographer has, as opposed to a print reporter? How do you deal with the privacy (and in many cases security) concerns of your subjects?

KA: I’m so glad that I started photography by shooting and processing my own black-and-white film. I didn’t have a great knowledge of the history of photography when I started out. I looked at classic black-and-white masters like Cartier-Bresson, the war photos of Horst Faas, Robert Capa, and the social documentary of the Works Progress Administration photographers. Josef Koudelka is one of my favorite photographers to this day. I came into contact with contemporary “war” photography while sitting through the Pictures of the Year Competition at the University of Missouri, where I went to graduate school. Viewing the judging of big photojournalism competitions is a humbling experience. There are so many brave and talented people around the globe bearing witness to incredible things. I just assumed, after seeing the work entered in that international contest, that all photographers sought out far-flung events that otherwise went unknown. It seemed so impossible and important at the same time. I still think that’s true. I also don’t consider myself a war photographer. I cover some stories like that, but I think the longer I work, the more I see crisis, and hope, everywhere. There are plenty of quieter stories all around us that deserve attention and have insights to offer.

The difference between photographers and reporters is that we have to be there in a place when events are unfolding to tell our stories. We can’t report on the phone or make interviews later. It’s important for us to be there, on the front lines, to document what others can’t access. It’s also important for us to step back and delve more deeply and to be contemplative. No single image can tell the whole story. But we have to go out where the stories are unfolding, to spend long hours to get what we’re after. We must develop relationships with our subjects and spend a lot of time with them until they become comfortable with our role.

Privacy is something photographers deal with on a case-by-case basis. Every once in a while, someone’s privacy is less important than the image that needs to be seen, such as something significant happening on a crowded street. But in most cases, if people don’t want their photographs taken and you do it anyway, the images aren’t going to be very good. We’ll see the reactions to our cameras, not to the situation, in those pictures. It may be an unspoken permission we have at times, but there is usually some sort of consensual relationship developed very quickly. The world is getting more sophisticated about imagery all the time. Many people have a fair idea about what photographers are up to. Ideally, people want you to share their stories with others. If it’s a long-term project, where I’m returning many times to the same people, then it almost becomes a collaboration. Other times it’s better to photograph first and get out before anyone tries to exert censorship or false authority stops you. Sometimes it’s a value judgment. Some countries have their own laws and codes, such as France. Each situation is different.

In Iraq, people knew why the media was there, and often were very willing to be photographed once they trusted that the journalist was a neutral or honorable party. Building trust in relationships can make or break your work.

H: How would events since your stay in Iraq—the full-blown civil war in 2006–7, followed by the uneasy relative stabilization since then—–change what you photographed or chose to represent, and the meaning of those earlier pictures? In retrospect what effects, both intended and unexpected, do you feel your work has had?

KA: I have often wished that I worked more in Iraq, that I spent more time documenting what it looked like, simply physically, before all the dramatic changes that followed. I wish I’d photographed more landscapes, architecture, sacred places. I loved the vegetable markets and I wish I’d photographed them more. I wish I’d photographed more living rooms and more scenes of daily life. I’m glad I photographed scenes of grief, anger, fear, and horror—people respond to these pictures. But without the context of images of daily life, these images are in danger of becoming isolated and incomprehensible.

It occurs to me that the people who influenced my understanding the most were not those who I encountered briefly, but people who I got to know better. The people whom I trusted, who helped me get around, who fed me dinner, and joined me shopping had the biggest impact on me. Hospitality is a powerful force. Codes of hospitality can engender mutual respect. It’s a lesson I’ve learned in Iraq and other places. Strangely, my time in Iraq gave me faith in the ability of people to transcend political barriers and see each other as individuals. Even under immense pressure when no one should have trusted me, people did. I treasure the time I spent in Iraq. I’m grateful for the faith people had in me and for the relationships that helped me build an understanding of the country.

As far as the impact of the photographs I made in Iraq, I only know what people tell me from time to time. People have said that they see photographs in our book, or in a slideshow that I present in a lecture, that they don’t normally see from Iraq. That’s strange to me because many of the photographs I’ve made were published in mainstream newspapers and magazines and there are so many other powerful photographs out there. Perhaps people experience the photographs in a different context when they hear me tell the stories behind the images, and they can ask me questions in person after a presentation. In the book, there are texts, quotes, some essays, and a framework that provides support for the images. I hope that the book helps slow people down and gives them some time to reflect on the subject matter.

H: How does one create images that place subjects “in context” without either being didactic or risking that the context will, in fact, be invisible to an audience that does not already know how to read it?

KA: Photographs have both universal appeal and limitations restricted to the experiences and perceptions of the viewer.

There is never any guarantee that viewers will take away what you intend with a photograph, and at some point, if your photograph survives in the public record long enough, it will be placed in contexts well outside of its original use. So there is no curtailing that risk. Increasingly, photographs are like space debris orbiting the planet electronically. I tend to think that ultimately, we have very little control over how our images are read, particularly those images that are republished without our comment. They will be different in each context and over time. The hope is that there will always remain a few people who will know or learn how to read them.

When I’m working on a journalistic project, I try to imply social, cultural, and physical observations. I hope to suggest a time and a specific place because, in the short term, people will look to these pictures to help them understand events. Working journalistically, I like to include text with my images providing context that visual information alone can’t supply.

I try to spend enough time that I become familiar with the themes, concerns, and trends in the place where I’m working. I look for scenes that repeat themselves. I watch and listen to how people react to events and try to record significant details. I hope to find visual themes or moments that might also resonate metaphorically in some way, that are clear images on the surface, but also contain some ambiguity and space for contemplation as well.

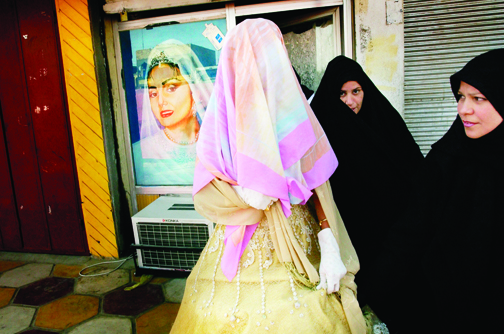

One photograph with some of these qualities is an image from Iraq of a woman leaving a salon with a scarf draped over her entire head. She’s wearing an elaborate dress—a viewer may guess that she’s a bride—and two women wearing conservative black abayas are leading her. The women in black are glancing around them cautiously as they step out of a beauty salon into the street. I clue viewers to the location by including the salon window in the background. A painted sign of a woman wearing makeup and a wedding veil are visible. The women’s expressions are important and reflect the anxiety women in Baghdad were feeling thanks to threats from roaming vigilantes who had begun to enforce conservative rules targeting how women dress in public. The bride may very well have been modest and covered her face to keep men other than her husband from seeing her on her wedding day. This was a custom at the time among some families in Baghdad, as I understood. But it’s not a typical veil so it also might imply that she’s hiding.

In the months that followed, salons were targeted for bombings. The Sadr militia threatened owners and told them to paint veils over women’s faces. The militia’s advertisements told them to stop applying makeup to women for parties and weddings. These specifics are impossible to explain in the image, but some of the mood, the texture, and the various modes of cultural dress are more evident. Alongside text, the image will be viewed in a more specific context.

At other times, the point of a photograph is more didactic. For example, the photograph of a demonstration outside of the Green Zone in Baghdad, the compound where the U.S. embassy is located, depends on actual words in the image to convey a message. A sign reads “Take All Instructions from Guards, Deadly Force Authorized”; and in the background, hundreds of people are bent in prayer. I’m sure most of the crowd of people were not aware of the sign, but the demonstration, in juxtaposition with the sign, appears to convey a peace offering in the face of authoritarianism. Demonstrators asked U.S. forces to refrain from engaging the Sadr militia in Najaf who had seized control of the center of the city and the Shrine of Imam Ali. It was a standoff. The Americans didn’t back down; and in the end, there was a three-week battle. The image tells us none of this, but the standoff, the American ultimatum, and the cultural and political confrontation are implied, I hope.

H: What does the market for “war photographs” demand? What is your sense of what is picked up, and what is not, what sells and what does not? How does that contribute to what the “iconic” images of a conflict become? What does this mean for persons in your position, in terms of viability of doing such work?

KA: There is far less of a market for images of war than people might expect. Wars are usually not news in the U.S. for very long unless the U.S. has a stake in the region in some way. If our troops are on the ground, it’s big news. There are wars all over the globe at this moment that we rarely hear about and it’s not easy for journalists, freelance or otherwise, to get stories about those wars in the news. The market for war imagery is really very small.

The iconic images of conflict that people in the U.S. might recognize reflect this. There is the image of the flag planting at Iwo Jima by Joel Rosenthal; the photo by Nick Ut of a young Vietnamese girl running down the road, covered in Napalm; the image by Eddie Adams of a South Vietnamese commander assassinating a captive; the image of September 11 firefighters raising an American flag in the rubble of the World Trade Center. That last photo is not an image of war, but rhetorically it calls to mind the image from Iwo Jima because of its visual similarities—so in an American context, it implies war.

These images are about American concerns, made during defining historical moments that impacted domestic audiences. That’s why they are icons. They are like personal reference points, visual shorthand that carries more or less baggage depending how much the audience knows about the actual times and places in which they were made.

For each photographer, those resonant images from a situation may be different, while editors or audiences may find images meaningful that don’t necessarily represent the events of the day. I don’t really look for iconic images that resonate with domestic narratives of the publication. If anything, I think I try to look for images that might surprise a domestic audience, that reflect what I’m witnessing, and which might be a road map for people seeking clues to a story they don’t know much about.

I hope to inspire people to dig deeper. An image is only a starting point. The image of the U.S. troops toppling the Saddam statue on April 9 is a good example of a moment that didn’t necessarily reflect the most significant events on the ground. That moment was certainly not the end of the war: the real fighting had hardly begun yet, but the image seems to suggest an American victory, or the toppling of one order by another force. While that photo was made, Baghdad was burning. Museums, schools, and hospitals were being looted. A photograph can’t possibly tell the whole story; it’s only one moment in time. Photographs are road signs. Events are always much more complex than we can possibly reflect in images. I find the best photographs suggest that complexity.

H: War photography has traditionally been a very macho endeavor, but of course there are many great women war photographers, starting perhaps with Gerda Taro during the Spanish Civil War and Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White during World War II. Do you see yourself as belonging to a lineage of specifically female war photographers, and if so, what does that mean to you—what do women bring distinctively to war photography?

KA: I don’t really think of myself as a woman photographer. I’m just a photographer. At the same time, I recognize that it’s only during my generation that women photographers have became much more common; and even now, there is something of a boys club to be sure. I admire the women who’ve come before me and pushed boundaries. I’ve been told by an editor at a photo agency that he didn’t want to sign a woman in her thirties because women only work as photographers until they are forty and after that, they want to stop working and settle down. It made me angry at the time but now I have to laugh.

I know plenty of male colleagues who have families, but that won’t stop them from traveling for long periods—they just leave their wives home with the kids! The fact that women still bear the responsibility of most child rearing probably contributes to fewer women pursuing a long-term career in conflict photography than anything else, but even that is changing. So long as most societies are patriarchal, there will be advantages and disadvantages to being a woman in the field. The advantages are that we tend to appear less threatening to men, and may raise fewer suspicions at times.

We also get better access to other women. We’re confusing—we act and dress like men but we’re not. In some cultures, strange men are not allowed to be in the same room with local women, while we tend to get treated as what I call “the third sex” and are invited into both women’s and men’s spaces. We’re often excluded from local restrictions as outsiders. Perhaps women have more of an insider’s understanding of women’s issues related to health, gender discrimination, and so on, but I’ve seen some men cover stories about women with incredible empathy and access.

So I think the biggest challenges remain those we face in our own cultures and at times among our colleagues. Things have come a long way since Gerda Taro’s day, but it’s still not uncommon to find women turning to their male colleagues to open professional doors for them.

NOTES

1. See “Iraq: The Media War Plan,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 219, edited by Joyce Battle (posted online at http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB219/index.htm), and Jeff Gerth, “Military’s Operation Is Vast, Often Secretive” New York Times, December 11, 2005.

2. David Benjamin, “Censorship in the Gulf” (1995) (posted online at http://web1.duc.auburn.edu/benjadp/gulf/gulf.html).

3. See Shahira Fahmy and Thomas J. Johnson, “Embedded versus Unilateral Perspectives on Iraq War,” Newspaper Research Journal 28, no. 3 (Summer 2007): 98–114; Cynthia King and Paul Martin Lester, “Photographic Coverage during the Persian Gulf and Iraqi Wars in Three U.S. Newspapers,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82, no. 3 (Autumn 2005): 623–37; and Jim Naureckas, “Gulf War Coverage: The Worst Censorship Was at Home,” Extra! 4 (Special Gulf War Issue) (1991), rpt. in The FAIR Reader: An Extra! Review of Press and Politics in the ’90s, ed. JimNaureckas and Janine Jackson (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1996).

4. Eric Schmitt, “Five Years Later, the Gulf War Story Is Still Being Told,” New York Times, May 12, 1996.

5. For the ”Media Embed Process” see the official website of United States Forces-Iraq, http://www.usf-iraq.com/?option=com_content&task=view&id=10215&Itemid=144, which includes the form required of embedded journalists: http://www.usf-iraq.com/images/stories/For_the_media/USF-I%20Hold%20Harmless%20Agreement%20January%202010.pdf.

6. See Thorne Anderson et al., Unembedded: Four Independent Photojournalists on the War in Iraq (White River Junction, Vt: Chelsea Green, 2005).