We're thrilled to learn that Katherine Lebow is the winner of the Polish Studies Association's Aquila Polonica Prize for 2013 for her article "The Conscience of the Skin: Interwar Autobiography and Social Rights" (Humanity 3:3 [Winter 2012]: 297-319).

The demise of international criminal law

We theorists of international law like to pose venturesome, vitalizing questions, sweeping in scope: What would an ideal system of international criminal law look like, for instance, relieved of today’s geostrategic constraints? How might we lend some conceptual coherence to such a program, flesh out its normative details? What kind of world would be required for such a program to become possible, even intelligible? How should we imagine the workings of such a hypothetical world?

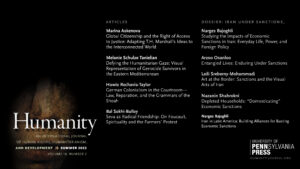

Humanity 4.3 is out

Issue 4.3, featuring a dossier on visual citizenship, is now available!

Dignity in general and in American constitutional law

This week The Nation published my essay on the origins and trajectory of human dignity, in which I engage absorbing and accomplished books by Michael Rosen and Jeremy Waldron.

The duty to reflect, still cogent

In a recent opinion column (“The Duty to Protect, Still Urgent,” New York Times, September 13, 2013), Professor Michael Ignatieff, speaking on behalf of “those of us who have worked hard to promote the concept” of a responsibility to protect, passionately argues in favor of the use of force in Syria and more generally each time “civilians are threatened with mass killing.” Although he admits prevention through conflict resolution and legality via a Security Council vote are preferable, he observes that “when prevention fails, force becomes the last resort,” and “if the United State

What is remedial intervention?

While the planned attack on Syria now seems to be deferred, the administration’s arguments supporting it will likely resurface. These arguments have admittedly been somewhat stuttering. Yet they will almost inevitably remain resources to be pulled up and reused, sooner or later. What can be said about the intervention’s purported justification from a human rights perspective? And perhaps more to the point, what would that perspective be?

Unembedding War Photography: An Interview with Kael Alford

The Iraq war has certainly blurred the distinction between reporting and waging war, turning information into a strategic weapon. It also triggered the beginning of ‘‘embeddedness’’ as a new military practice of control, first with journalists, but now extended to civilian researchers such as anthropologists. Kael Alford tells us how her ‘‘unembedded’’ project was conceived.

In the name of security

“This norm against using chemical weapons,” explained Obama in his Tuesday Remarks Before Meeting with Members of the Congress, “is there for a reason: Because we recognize that there are certain weapons that, when used, can not only end up resulting in grotesque deaths, but also can end up being transmitted to non-state actors.”

Humanity 4.2 is out

Issue 4.2, featuring a symposium on human rights history organized by Humanity board member Jan Eckel, is now available!

Michael Ignatieff’s critique of human rights (and other scenes from the National Humanities Center)

It was the first few pleasant moments in a two-day event, the second annual “Human Rights and the Humanities” conference at the National Humanities Center, held in March 2013. Greetings had been extended, sponsors thanked, the distinguished keynote speaker introduced, and the audience settled in. But almost immediately the speaker was parting company with many in his audience. His title was “Do States Have the Right to be Wrong about Justice?,” and the argument, surprising and disturbing to many in the room, was that yes, they did.